Benjamin Nathans explores the phenomenon of academic dissidence in the USSR.

Dmitry Dubrovsky

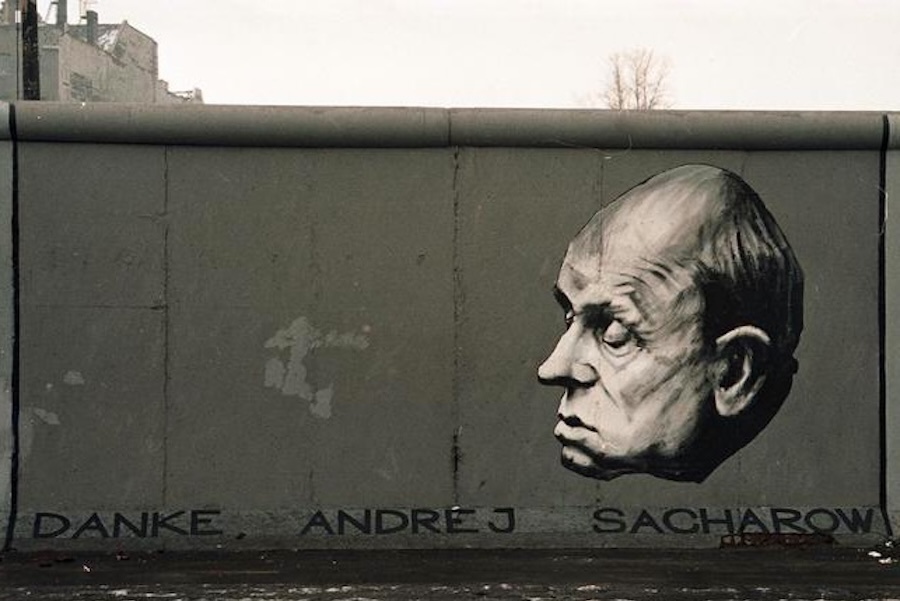

Photo: Andrei Sakharov had his own “stumbling block.” Photo by Re2000 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=106564383

The situation with academic rights and freedoms in Russian academia increasingly evokes associations with the Soviet era, and the repression of scientific researchers, teachers, and students shares similarities with the persecution of Soviet scientists. To better understand the current situation, it is useful to understand the specific forms that resistance to ideological pressure and repression took in Soviet science and higher education—namely, academic dissidence.

The Path to Dissidence

The path to academic dissidence sometimes began with a serious violation within academia.

Other times, academic dissidence resulted from scientists protesting as citizens, and thus represented a reaction to injustices committed by the authorities, not the scientific top brass.

Finally, a distinct form of academic dissidence came as a result of persecution for expressing solidarity with repressed colleagues.

Research

Academic dissidence in the USSR is a well-known but apparently insufficiently studied phenomenon. Existing publications generally focus on the human rights movement as a whole.

The academic component—that which is commonly referred to as academic dissidence—is generally represented by publications related to intellectual opposition to the Soviet regime (for example, the works of Barbara Martin, Mick Cox, and Pyotr Druzhinin). All of these excellent works are based on the study of biographies and specific cases related to academic or, more broadly, intellectual resistance to Soviet power.

That being said, virtually the only work that attempted to generalize the forms, practices, and transformation of academic dissidence in the USSR was frankly unsuccessful and was not continued.

A major contribution to the study of intellectual resistance is the recent monograph by University of Pennsylvania historian Benjamin Nathans, To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause.

Moral Choice

The book is devoted to the human rights movement in general, but it describes, in particular, the reasons that pushed Soviet intellectuals to embrace resistance and dissent. Nathans, following Bukovsky, calls these stories “stumbling blocks.”

A stumbling block is a situation in which a Soviet scientist faces a moral choice: agreeing to something they consider morally wrong, or disagreeing, which comes at the cost of dismissal, pariah status, persecution by the state, or emigration. In the Soviet Union, this was a very high price.

Academic dissidence can be defined as criticism or resistance to the state, its policies, or practices within the academic community. Academic dissidents, therefore, are individuals whose stumbling block lay within academia, who joined the human rights movement, or simply supported those persecuted—and, as a result, faced repression themselves.

The Case of Nekrich

Alexander Nekrich encountered his stumbling block within Soviet academia. A professional historian, he wrote a scholarly work, “June 22, 1941,” about the causes and first months of the Great Patriotic War (as the Second World War is known in Russia). He found that his professional assessment was dangerous to the Soviet Party elite, who were unwilling to acknowledge the book’s main conclusion: the country’s leadership—especially Stalin—had been unprepared and criminally negligent, and had disregarded intelligence data regarding the outbreak of war.

Nekrich stood by his conclusions and failed to “repent before the Party.” This resulted in his expulsion from the Party and disgrace within the Institute of History, where, according to contemporaries, it was forbidden even to smoke around him. As a result, Nekrich used his Jewish heritage to emigrate from Russia and settle in Boston, where he lived until his death in 1993.

Tellingly, those who stood up for Nekrich in academic discussions were also severely punished. For example, Professor Melamid, who praised the book during a discussion and called it successful, was reprimanded by the Party, a serious punishment at the time.

Thus, not only having “incorrect views,” but also supporting those of others, could spell the end of a Soviet scientist’s career.

Leonid Petrovsky, a young historian at the time, fell victim to the same fate when he compiled a “brief record of the discussion of Nekrich’s book at the Institute of Marxism-Leninism under the Central Committee of the CPSU on February 16, 1966.” Petrovsky was dismissed and later summarized his record as “…three books, 500 articles over 20 years, excommunication from graduate school (as a candidate of sciences), five heart attacks, and a meager pension.”

Thus, a reluctance to support the campaign to suppress dissent could—and did—become another stumbling block. Even timid attempts to speak out against it ended tragically for those trying to protect friends and colleagues.

The Case of Fast

Wilhelm Henrikhovich Fast, whose entire family was subjected to Stalin’s purges, was dismissed from Tomsk State University in 1982 for refusing to testify against a colleague in a trial for “anti-Soviet propaganda.”

Following this refusal, a special ruling was issued ordering that he and another university employee, Gennady Novikov, be convicted and that “appropriate measures be taken.”

A committee urgently convened at TSU to evaluate Fast’s work determined that although he “is a highly qualified specialist” and works at the “proper theoretical level,” his ideological and political stance was manifested in his “refusal to participate in atheistic propaganda (Fast is a believer) and his failure to participate in elections to Soviet government bodies.” Most importantly, he was accused of a “lack of principle in assessing the anti-Soviet activities of his friends.” Rector Bychkov dismissed Fast based on the committee’s findings.

The fact that Fast’s story cannot be found in the archives of Tomsk State University is telling, particularly when everyone who signed this act continued to work prosperously at the university as professors and leading staff members. Fast himself worked as a janitor and beekeeper for seven years, returning to his field of specialization only in 1989. He became a co-organizer of the international historical and human rights society Memorial in Tomsk, became friends with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and spent the rest of his days working at the Solzhenitsyn Foundation in Tomsk.

Not the First Time

The first attempt to overcome the stumbling block is not always successful. Poet Natalya Gorbanevskaya, who participated in a legendary 1968 demonstration against the deployment of Soviet troops to Czechoslovakia, tripped over her first stumbling block in 1957. While involved in a legal case against students distributing leaflets to protest the invasion of Hungary in 1956, she, by her own recollection, “started to stereotype these guys…and at the trial I was the only witness for the prosecution…this is the darkest moment in my life, which I have not forgiven.”

Perhaps this experience contributed to her decision to join the protest against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Other “Blocks”

These blocks presented themselves differently for such well-known dissidents as Andrei Sakharov and Sergei Kovalev.

For father of the hydrogen bomb Andrei Sakharov, his stumbling block came when he gained a scientific understanding of the scale of the harm imposed by nuclear testing. This inspired him not only to actively fight against the technology, but also to conceptualize it in terms of human rights and to help those persecuted for their views. His text “Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom” posits the violation of intellectual freedom as a global problem and censorship as one of its main threats.

Sergei Kovalev faced his own stumbling block at the beginning of his path as a dissident: his protest against Lysenkoism cost him his academic position. He recalled that while working in the biology department at Moscow State University, he realized that Lysenkoist nonsense (“if you feed any bird hairy caterpillars, they will hatch into cuckoos”) was mandatory instructional and exam content. Kovalev countered with a scientific mind: “We were taught Michurinist biology and genetics, but this was radically different from what was taught elsewhere. You train scientists, but scientists must have a comprehensive understanding of the problems they intend to address.” Thus, the conflict centered on the principles of scientific knowledge, which the Communist Party had replaced with Lysenko’s ideological “communist” science.

In February 1966, the verdict in the Sinyavsky-Daniel case prompted Kovalev to appeal to the Presidium of the Supreme Court. He collected signatures for the appeal, and from that moment on, he began openly advocating for human rights. Thus, in Kovalev’s case, his “stumbling blocks” were both science and social injustice.

To Sign the Letter…

Needless to say, for many, their stumbling block was signing a letter of protest.

Following the trial of Sinyavsky and Daniel came the trial of Ginzburg, Galanskov, Dobrovolsky, and Lashkova. This led to the publication of a series of letters of protest, which formed the so-called petition campaign.

One of these letters, the “Letter of Forty Six,” signed in Novosibirsk in 1968, contained no particularly seditious content—it simply expressed protest against closed political trials and concern about the practice in general, which was clearly associated with Stalin’s lawlessness. It concluded with a call to overturn the sentence and reopen the case in a fully transparent manner.

After this letter hit the foreign press, repressions began in Novosibirsk’s Akademgorodok. Party and public meetings led to layoffs and a significant change in the atmosphere of the entire scientific town, which had been renowned for its vibrant atmosphere.

One of the authors of this petition, Leonid Lozovsky, explained during one of these meetings that he, a physicist, was compelled to write a public letter by the reaction to the trial of foreign communists and his concern that “there were violations during the process.” During the debate, it was stated that the letter’s author “was motivated by an organized, well-paid force” and “was not worthy of being a member of our collective.” At a closed Party meeting, the following opinion was expressed: “People who appeal to America deserve contempt. Those who handed the document over to America must be condemned.”

Lozovsky and the other authors of the letter were fired. Lozovsky himself was forced to leave the country. The other signatories were expelled from the Party or Komsomol, or issued severe reprimands. Others were suspended from teaching or fired.

Abram Fet was fired and remained completely unemployed for four years. George Zaslavsky, mathematician and linguist Alexey Gladky, historian Marina Gromyko, mathematician Gleb Akilov, and philologist Maya Cheremisina were also dismissed. Those who remained employed found their lives seriously complicated, hindered by obstacles to publication, dissertation defenses, and career advancement. Finally, the Under the Integral Club in Akademgorodok closed, marking the end of the thaw in this unique scientific city.

* * *

Despite the danger, support from colleagues continued throughout the era of confrontation between dissenters and Soviet/Party authorities. The stumbling block could be either a violation of academic freedom or a violation of freedom overall.

The academic and party leadership responded with dismissals, created obstacles to their work, directly prohibited professional activity, and even opened criminal cases.

For many, their stumbling block was seeing what was happening to their academic colleagues. Simple support for colleagues or outrage at their colleagues’ situation led them into political confrontation with the authorities.

Benjamin Nathans formulates this position as the principle of “behaving like a free person in unfree conditions.” This principle was linked not only to a willingness to protest, but also to the development of an ethical norm for protest that combined science—legal literacy, accuracy and verifiability of facts—with a willingness to pay the price for taking an ethical stance.

Scientists in the USSR created a unique moral position that could be defended through scientifically formulated arguments and verified facts.

0 Comments