How universities around the world are escaping authoritarian pressure and disaster

Part 2.

Sofia Smyslova

Photo: Some researchers argue that leaving is the only and most powerful way of opposing the authoritarian regime. Photo by Michal Balog on Unsplash

In Part 1, we discussed how universities and scientists survive authoritarian governments by going underground and deformalizing. Part 2 is devoted to another strategy—relocating the educational institution outside the geographical boundaries of the authoritarian state.

Relocation

While going underground entails a drastic transformation of the academic process (and most often imposes limitations that result in deformalization), relocating is a way for academic institutions to preserve themselves in a relatively pristine form.

The idea of relocating higher education institutions remains a controversial proposition. It raises questions about the nature of the university and its relationship to the government/national context:

- Can a university really relocate—that is, move from one national/public content to another?

- Or does this constitute the creation of a new institution (even if it is very similar to the old one)?

On the other hand, some researchers argue that leaving is the only and most important way of opposing an authoritarian regime (O’Connell, C., & Long, K. (2024). Exile Institutional Response Authoritarian Interference. International Higher Education, 37–38)

Ties to the Homeland

Thus, a university in exile differs from a simple university—any university established abroad—in that it is physically displaced under duress and, despite resuming academic activities elsewhere, maintains strong ties to its homeland. It is precisely this connection to its original context (and not merely its orientation within a new social and geographical space) that distinguishes a university in exile from an educational project established abroad, even one founded by individuals from the same ethnic group.

These ties can take various forms.

Goals for the Future

One of the most vivid examples of this in Russian history occurred following the October Revolution, when a wave of emigration in 1917-1919 led to the establishment of a whole series of alternative educational institutions. Although oriented toward the specific needs of the ever-growing emigration crisis, many of these institutions articulated a specific goal for the future that was tied to the homeland:

“…when [we] can return and build a democratic society” (Bulanova, 2011, p. 177).

The idea of building a better future, or preparing the intellectual foundation for it, has also emerged frequently in the modern history of universities in exile. This is how Spring University Myanmar, founded after the military coup in Myanmar in 2021, formulates its mission:

“…to empower young people to lead, collaborate, and thrive in a free and democratic society.”

And this is from the mission of the American University in Afghanistan (which moved from Kabul to Qatar in 2021 after the Taliban came to power):

“…to empower rising leaders with the knowledge, skills, and agency to determine their own individual and collective futures.”

A similar sentiment is expressed, if less explicitly, by the European Humanitarian University, which was forced to relocate from Belarus to Lithuania in 2005. This, incidentally, distinguishes it from another frequently cited example of relocation among European universities—the Central European University (CEU), which left Budapest and reopened in Vienna in 2019. In its official communications, the CEU makes no mention of the relocation story, and the rector emphasizes: “We are not moving to Vienna to be a university in exile.”

Both EHU and the burgeoning Free Belarusian University, based at the University of Wrocław in Poland, are focused on supporting and developing Belarus “after.” The latter university aims to “train personnel for reforms in the future of Belarusian society.”

Another example that is a new institution, but still conceptually “in exile,” is the Boris Nemtsov Academic Center, which has been implementing two projects at Charles University in Prague since 2022:

- a Master’s program: “Russian Studies—Boris Nemtsov Educational Program”

- the Ideas for Russia research project

The orientation toward the original national context appears as a “preparation for the future,” even if this future may never arrive.

A “Safe Haven”

Another thing these ties to the homeland may signify is a “safe haven” for those who leave the country due to disaster, war, and/or authoritarian repression.

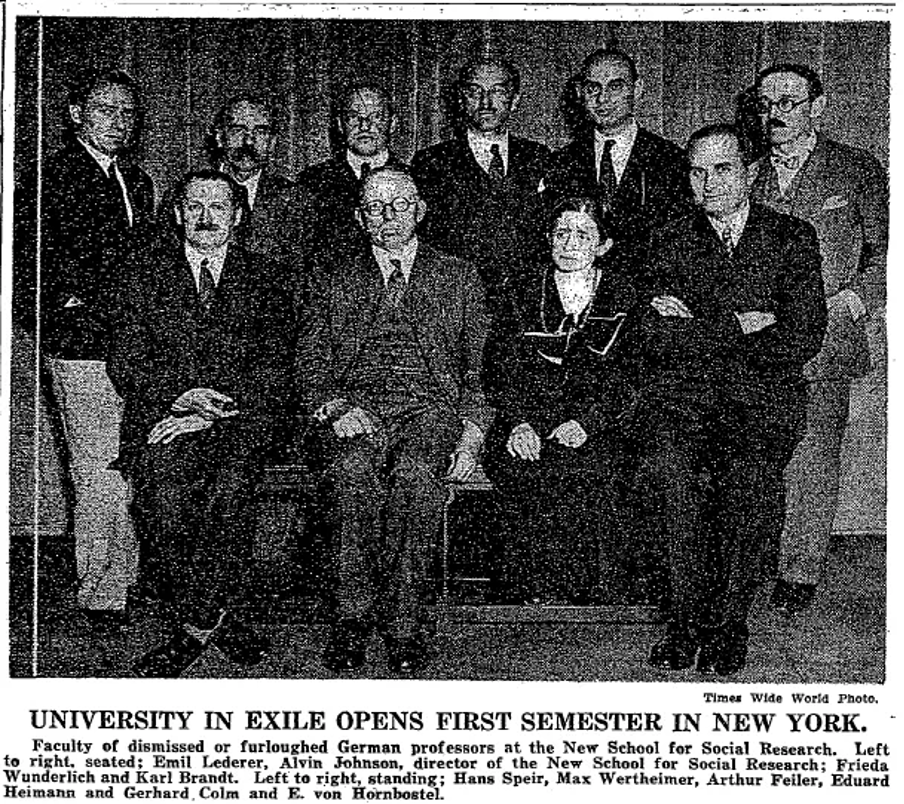

The most iconic example of such relocation into exile is the mass exodus of scientists from Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1939. Although many of the academic refugees subsequently built personal academic careers in international academia, some of them joined (or, more accurately, were integrated into) the same intellectual circles as in Germany.

Thus, for example, The New School in New York arranged for the relocation of nearly 200 academics, and with their help created a social sciences and humanities research and teaching unit. It was also at this time that the term “universities in exile” appears to have been coined—this was the name given to the departments to which European professors were recruited. (The latter were usually Jews, but not always; one notable example of relocation by a non-Jewish person was the law professor Arnold Brecht.)

The invitation (or evacuation) of German professors was undoubtedly a life-saving mission. However, some historians argue that for Alvin Johnson, co-founder and director of The New School, it was also a very important recruitment campaign.

Before the Nazis came to power, German universities were global intellectual leaders, and this new affiliation with leading academics gave The New School, which had been founded just 15 years earlier, a huge boost. Erich Fromm, Max Wertheimer, and Aron Gurwitsch were among those who relocated to the United States. After the war, Hannah Arendt joined the faculty, and Ernst Bloch attended weekly seminars.

Despite its controversial contribution to German “brain drain,” the University in Exile at The New School became an important base for escaping scientists. Many of them returned to Germany after the fall of the Nazi regime.

In a photograph published in the New York Times on October 4, 1933, Johnson sits second from the left, flanked by Emil Lederer and Frieda Wunderlich. Behind him, also second from the left, stands Max Wertheimer, one of the founders of Gestalt psychology.

Other universities in exile also serve as islands of salvation. For example, Off University, founded by Turkish academic émigrés after 2017, defines its mission as providing a “digital refuge […] for scholars in danger.”

The Modified Practice of “Salvation”

The increasing mobility of academics, the globalization of international academia—primarily European and American—and authoritarian outbreaks in various regions have led to the creation of a variety of programs to assist at-risk scholars (SAR, CARA, PAUSE). The New School created in 2021 its own support program: The New University in Exile Consortium (NEIUC), a coalition of universities that hosts several at-risk scholars on fellowships at partner universities.

However, contemporary academia is very different from the German (or any European) university of the early twentieth century. Some authors emphasize that this significantly modifies the practice of “salvation” (Özdemir, S. S., Mutluer, N., & Özyürek, E. (2019). “Exile and plurality in neoliberal times.” Public Culture, 31(2), 235–259, https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/90827/1/Ozyurek_Exile-and-plurality.pdf).

Unlike the University in Exile in 1934, NEIUC exists within a neoliberal university. A professorship no longer allows for a prestigious intellectual lifestyle. More and more positions are becoming part-time, conditions are precarious, and prospects are dim. There are significantly more PhD candidates than openings, which ultimately leads to hypercompetition.

In this process of marginalization of academic life, newly arrived scholars at risk (who were previously people with impressive track records and in good positions at their universities) find themselves not in a “comfortable Western academic environment,” but in a situation of competition with young American or European postdocs.

Third Space

Struggling with the loss of symbolic status and wishing to emigrate at least partially on their own terms, many exiled academics create their own educational or research spaces, outside of formal institutions (or with partial affiliation): the so-called “third space.”

The creation of an alternative academic space becomes a practice of preserving not only one’s accumulated baggage, but also one’s mental state (read more in my article on academic emigration).

Such alternative spaces most often become online learning spaces, which allows for the combination of elements of the first and second strategies through the format’s cross-border capabilities. The communicated key connection to the homeland is expressed as “overcoming borders” and access to uncensored, free knowledge—thus returning to the vision of the flying universities. Now, however, the movement occurs not through safe houses, but from physical reality to the virtual.

Examples of such cross-border movements include:

- the aforementioned Off University

- Smolny Beyond Borders, founded by members of the closed faculty of Smolny at St. Petersburg State University after 2022

- Free University, created in 2020 by faculty members of the Higher School of Economics who were dismissed or forced to leave

- Iran Academia, an online initiative for Iranian students and teachers barred from pursuing an education within the country

All of these projects primarily formulate their task as “providing access to free knowledge” and are oriented largely toward students who remain within the geographical boundaries of the original national context.

0 Comments