The experience of teaching public administration in an era of war

Kirill Shamyev

Photo: In the social sciences, it is easier to label propaganda as “science” by attaching the label of “sovereign” science. Photo by Brendan Church on Unsplash

An Alternative without Alternatives

One of the pillars of authoritarian politics is the feeling that there is no alternative to this path of political development.

As my experience has shown, independent projects focused on teaching the principles of democratic public administration and political analysis allow students to believe that there are alternative ways of effecting change in Russia. This is precisely why the government limits the ability of Russian citizens to discuss and find alternatives to the existing model of government and governance.

Following the invasion of Ukraine, the Russian political leadership, fearful of alternative explanations of its foreign policy, has intensified propaganda campaigns at universities. The pressure on independent-minded teachers has increased. The freedom to discuss socio-political topics is limited. A significant proportion of instructors have gone abroad, fearing persecution or the military draft.

The repression of social and humanitarian education not only suppresses the threat of Russia’s actions in Ukraine being delegitimized, but also has strategic societal implications.

Diploma or Knowledge?

In discussions about the potential for democratization in Russia, it is often said that Russian society as a whole is highly educated, which should reflect positively on the prospects of democratic development.

In reality, however, the formal presentation of a diploma from a higher educational institute does not necessarily indicate that the possessor has received basic socio-political and philosophical knowledge about the development of society, politics, and the state. Structural limitations (poor financing, lack of knowledge of foreign languages, the race to publish more papers) and political influence (“undesirable” research topics and the politicization of university administrators) push Russian social science teachers toward the fable of the so-called “sovereign sciences.” Under this system, it is easier to promote poor-quality or openly propagandistic material in the political sciences by tacking on the label “national,” “sovereign,” or “traditional” science. For every John Locke or Robert Dahl, you will find a Lev Gumilev or Ivan Ilyin.

The consequences of this mistake will echo for decades, as millions of civilians start to believe in the global conspiracy about the Club of Rome, the West’s desire to forcibly take away Russian resources, and other fictions. This is why a formal diploma from a higher educational institute by no means signifies an adequate level of knowledge about societal development in Russia.

How Democratic Public Administration Works

The Russian “New School of Political Science” project was founded in fall of 2022 with the hope that “in the catastrophic situation into which Russia has plunged, our school will ground our students, inspiring participants and preparing them for a future in which politics will return to the everyday lives of normal civilians.”

The public administration course I taught in 2022 aimed to foster a comprehensive understanding of

- what government is

- how politicians organize governmental work

- how they promote and advance reforms

The series of classes was based on classical political analysis courses conducted in American and European universities within the competency framework of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): flexibility, analytical thinking, and diplomatic tact. I wanted to show how democratic public administration works and explain why the “special Russian path” does not exist in the context of governmental operations.

At the beginning and end of the course, I asked students to take an anonymous survey where they wrote down three words they associated with the terms

- state

- politics

- reforms

The results were then organized into three pairs of word clouds.

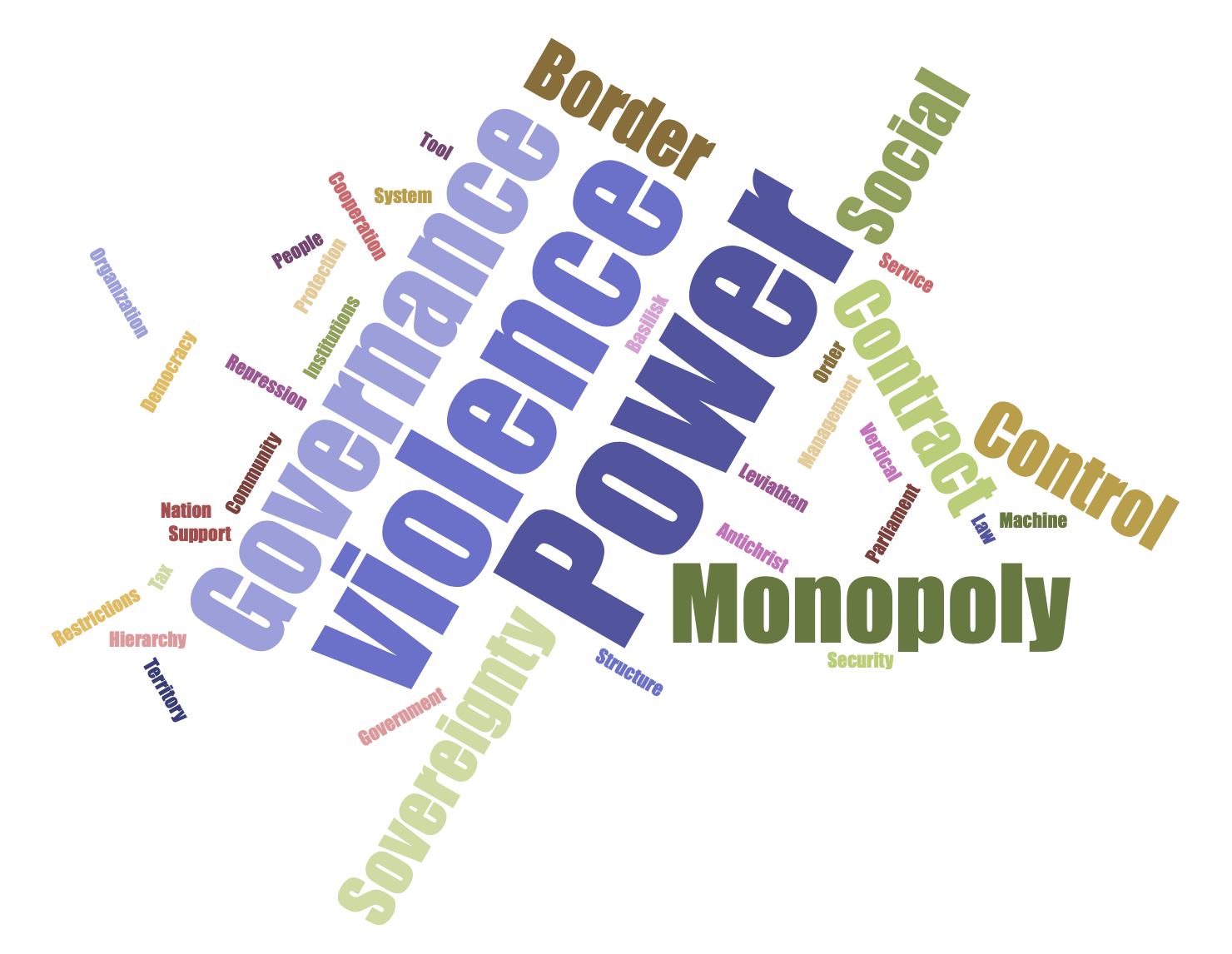

Associations with the Term “State,” Before and After

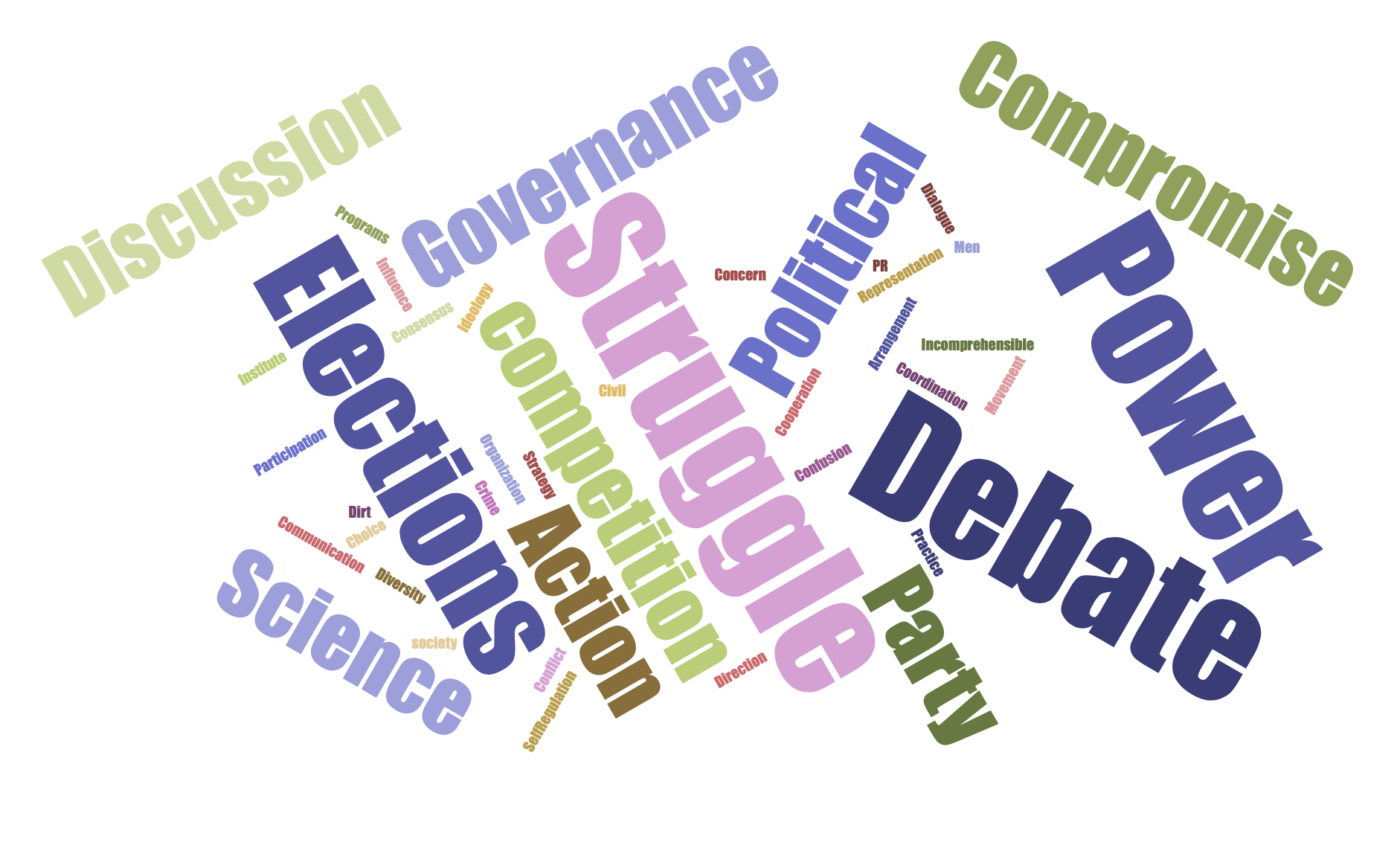

Associations with the Term “Politics,” Before and After

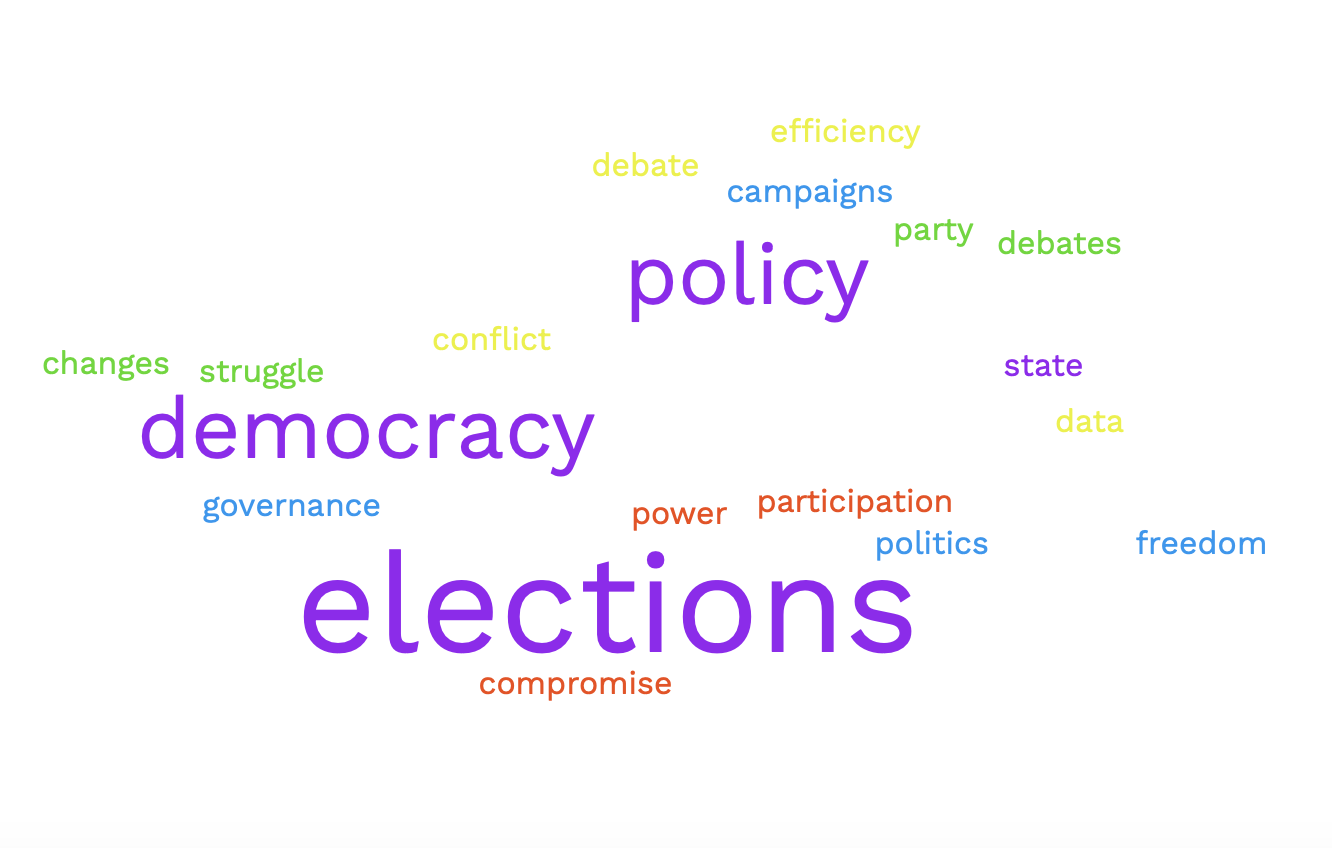

Associations with the Term “Reforms,” Before and After

Before and After

Overall, students of the course demonstrated a noticeable refinement of their understanding of the three terms.

State was at first associated with power, governance/administration, and violence.

After the course, however, the students associated “government” more with monopoly, sovereignty, and democracy.

This result resonates with my desire to show that the state does not have an unconditional monopoly and sovereignty in domestic politics, since in practice the state is created by active civilians who want to solve the problem of collective action.

Politics. A more notable change occurred in students’ understanding of the word “politics.” Before the course, students associated this term with governance, fight, power, debates, and compromise.

After the course, the most frequently associated terms were democracy, party line (i.e., a political party’s policies), elections, and freedom.

Politics and policy was the context of this public administration course. I showed the practical impossibility of an apolitical, “technocratic” government.

Reforms. Initially, students associated the term “reforms” with changes, improvements, development, and economic reforms.

At the end of the course, students continued to see change and development in reforms, but supplemented the word cloud with the additional associations strategy, cycles (political), and the names of two statesmen (Pyotr Stolypin and Aleksei Kudrin).

Their understanding of reform ceased to be econo-centric and associated with progress. In practice, reforms touch all spheres of public life and may actually run counter to progress.

At the beginning of the course, I talked about the fact that the reach of the state goes far beyond the sphere of money and wealth. It affects people before they’re born (prenatal care for pregnant women) and after death (rules of autopsy and burial).

Moreover, there are many tragic examples of regressive reform:

- women’s health reforms, including the Polish ban on abortion (2020-2022)

- electoral reforms in Putin’s Russia, such as the introduction of electronic voting in 2019

This simple survey beautifully demonstrated how current social and humanities education affects people and their understanding of the state, politics, and reforms. Students began to see the dynamics of political and governmental processes instead of simple static associations.

Using examples from democratic and developing countries, I tried to show that, on the one hand, Russian problems are solvable, but on the other hand, finding solutions to major socio-political problems requires politicians to take a systematic and scrupulous approach.

“Practical” Knowledge

Independent educational projects, such as the Free University and the New School of Political Science, “Renaissance,” and others are capable of opposing the decline in quality of the socio-humanitarian educational system in Russia.

As my experience has shown, this course will be relevant and useful for students if it connects “practical” knowledge about public administration, ways to analyze reforms, and the main components of the political process with democratic values and examples.

In the teaching assessment survey, several students stated that they have used the knowledge they acquired during the course in their work for businesses and non-profit organizations.

Limitations and Opportunities for Growth

New projects also face some serious limitations.

First of all, these courses can be taken by a relatively small number of students. The “drop in the ocean” problem is natural for educational projects and can be partially offset by the admission of the most motivated students, who are willing and able to apply and disseminate their knowledge in a leadership capacity.

In my opinion, targeting civic leaders and professionals with career potential for managerial positions should be a priority for such projects.

Second, democratic mainstreaming and focus on social change should be part of the foundation of any independent public education project in the social and humanitarian sphere.

False “neutrality,” where human rights or democratic politics are presented as “ideologies” and not as the most successful principles for organizing public life, only plays into the hands of the autocrats. Critical discussion that identifies the failures of these systems and finds solutions to these failures is part of democratic development. This plays the same role as crash testing and structural evaluation in engineering.

Third, independent social-humanitarian courses should become more sensitive on the topics of class, ethnicity, and gender. Insensitivity to distortions of social and humanitarian knowledge due to the exclusion from the analysis of the experiences of unrepresented groups of people makes the courses less relevant in modern conditions.

* * *

In sum, the feeling that there is no alternative to political development is the basis of authoritarian politics.

Teaching social and humanitarian disciplines focused on governmental change undercuts this monopoly. This, in turn, can create the ideological conditions for progressive collective action.

0 Comments