Part 2. Science and Higher Education in Putin’s Russia: From Recentralization to Hybrid Ideologization

Dmitry Dubrovsky

Photo: Stele “Glory to Soviet Science” (DNA monument) and the Blagoveshensky Annunciation Cathedral. City of Voronezh. By Vadim Indeikin, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54485039

In Part One, we outlined the logic of interaction between science, higher education, and power in the Soviet Union. In Part Two, we talk about Putin’s Russia.

Reforms of the 2000s

Academic reforms were initially aimed at making Russia an internationally recognized leader in higher education and science. The main objective was to gain recognition in the international higher education market.

It is important to note that the reforms were carried out by means of “authoritarian modernization.” This led to increased centralization and a decrease in the level of democracy and freedom compared to the 1990s.

The University Power Vertical

First and foremost, a vertical power structure was established in universities. For this purpose, elections for rectors or deans were in many cases replaced by appointments.

As studies show, where elections remained, they became “Putin-style” elections. The powers of the Academic Councils were seriously curtailed. At the same time, reforms within universities made the elected position of dean insignificant.

The quality of rectors subsequently fell—according to Dissernet data from 2019, almost one in every five rectors had violated professional ethics in one way or another. Of the hundred top Russian universities, half of the rectors were members of United Russia, and some were directly connected to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the FSB.

The First Departments, which had in Soviet times provided secrecy and ideological control, came back to life.

Finally, trade unions and student councils did not become tools for protecting academics and students. The few exceptions, such as the University Solidarity trade union, only prove the rule.

“Ethics commissions” that interpreted criticism of the state as “unethical behavior” began to be used as a tool of repression in universities.

Rosobrnadzor, created back in 2004, has proved a convenient tool of repression. Inspections of “state educational standards” have become an instrument for exerting pressure on universities, since “observed discrepancies with educational standards” can be used to justify denying or revoking an institution’s accreditation. This was the case with the European University at St. Petersburg, which was temporarily deprived of its accreditation.

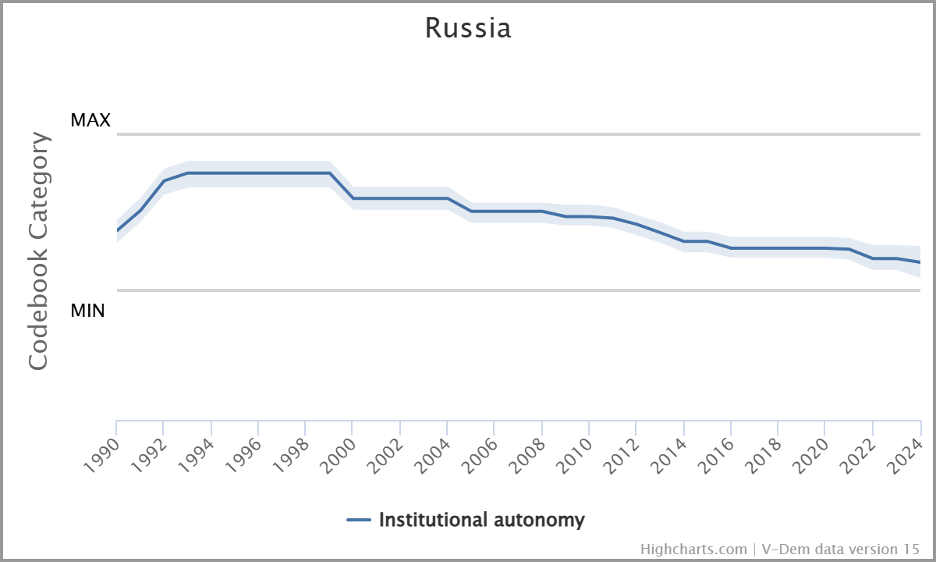

Thus, according to the V-DEM index, the level of university autonomy under Putin fell immediately following the start of the reforms (see figure). Since then, it has steadily declined to levels approaching those seen in Soviet universities in the mid-1980s.

Stripped-Down Science

Academic freedom was also impacted by the reform of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

In 2013, a new law redefined the RAS as a federal state budgetary institution established by the Russian Federation. As a result, its powers were significantly curtailed, while state reporting requirements became more stringent.

After that, the Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations (FASO) was created. The FASO was tasked with overseeing property and personnel issues. Two years after the agency began its work, the President of the Russian Academy of Sciences called the reform “the most radical and dangerous of those experienced by the Academy.”

Despite researchers’ protests, the reforms continued until May 2018, when, by presidential decree, FASO was disbanded and its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

One special direction taken by reforms in academic science was an attempt to integrate science into the market system—an idea that would have been unthinkable in the USSR.

Irina Dezhina notes that although Soviet models and practices were retained in the management of science, significant steps were nevertheless taken to create market economy instruments for academic science, and especially for the development of research. Foundations appeared, among them the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR) and the Russian Foundation for the Humanities (RFH). Their merger in 2013 strengthened the centralization and control of academic science by the state.

The difference from the Soviet system was the development of neo-managerialism without ideological content.

After 2012

The situation changed after the conservative swing in Russian politics that accompanied Putin’s official return to power in 2012. The main ideological focus became a clear anti-Western trend in politics. This trend was reflected in science and higher education.

At that time, the first victims of ideological censorship appeared, selected from the fields of human rights, political science, gender studies (particularly LGBT studies), and public sociology.

The first “national science” projects also popped up, for example the concept of “Orthodox sociology” developed by dean of the sociological faculty of Moscow State University V. Dobrenkov. Attempts were made to create Orthodox medicine and Orthodox psychology.

Particularly notable was the Russian state’s policy in the field of history: here, the turn toward “traditional values” meant an aggressive memorializing policy, associated primarily with the Second World War.

A special campaign to purge education of the “foreign influence of the West” sought to combat the artes liberales and, in essence, reframe the entire discipline as “undesirable” (along with Bard College, where it was developed).

One set of laws in this series that stands out from the rest is the legislation on “foreign agents” and “undesirable organizations.” These laws seriously affected Russian higher education and science, primarily international relations and some research organizations in Russia (for example, the Levada Center and CISR).*

* This law, originally aimed at legal entities, was later expanded. Many Russian scientists and teachers, including the author of this text, were, in addition to being slapped with this discriminatory status (which is accompanied by many humiliating requirements), banned from teaching within the Russian Federation.

Thus, the structure of control and censorship was already built before the war began. At the same time, the centralization of the management of science and higher education increased significantly.

After February 2022

The invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 changed the overall picture in a catastrophic way.

First of all, Russia abandoned the global education and science market. Sanctions, boycotts, and exclusion from the Bologna system led to this official statement by the Minister of Higher Education:

Russia will build its own “unique education system, which should be based on the interests of the national economy and providing the maximum space for opportunity for each student.”

At the same time, the vertical system of governance of science and higher education, originally built to implement neoliberal reforms and strengthen the recognition of higher education and science in the world, turned out to be extremely convenient both for carrying out repressions and for integrating the ideological project “DNA” (the “spiritual and moral component”) into the environment of higher education, the humanities, and social studies.

Even before the war, many universities had introduced the position of “vice-rector for youth policy” to strengthen control over students. Immediately after the war began, these positions were fortified. A clone of the department for combating extremism (referred to within the Russian police force simply as “Department E”) appeared in Russian universities. In the fall of 2022, new Coordination Centers (with longwinded names) were created by the Ministry of Higher Education to monitor the loyalty of students and teachers.

The “DNA of Russia”

In the field of humanities and higher education, we saw the first project claiming to be a general ideological project.

The “DNA of Russia” project was developed per the instructions of the president by the expert methodological council of the State Council commission, in collaboration with the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation in the Field of “Science.” Within the framework of this project, they formulated the task of creating a “block of humanitarian disciplines constituting the ‘DNA of Russia’” and the course “Fundamentals and Principles of Russian Statehood.”

Significantly, the project was developed not by the academic institutions of the Russian Academy of Sciences but by the leading universities of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education: Moscow State University, St. Petersburg State University, and the National Research University Higher School of Economics, coordinated by the “Expert Institute for Social Research.” In 2022, the head of the project, Andrei Polosin, clearly expressed the foundation of ideological control and the focus of the project as a whole:

In the context of global ideological confrontation, the role of education becomes a matter of choice for the younger generations and the survival of the state. Understanding this formed the basis for the creation of an educational ecosystem from grade school to university. Today, it includes the DNA of Russia Project, updated courses and textbooks on history, the Fundamentals of Russian Statehood course, education advisers, vice-rectors for youth policy and educational work, and other components.

“Fundamentals of Russian Statehood”

In particular, there is the Fundamentals of Russian Statehood course. Since 2023, it has been a mandatory course in all universities in the country.

This course, according to researchers, was the starting point for crystallizing the official ideology of Putin’s Russia. Its main content is a set of modern political narratives from Putin’s propaganda, from the “country-civilization” that allegedly peacefully annexed “friendly peoples” during its conquests, to the direct justification of Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine.

Judging by the reading list and content, the main ideological goals of the DNA project/Fundamentals course do not represent a challenge to the world system, unlike the ideology of the USSR. It is an attempt to build an ideology of exclusivity based on generally Western theoretical approaches, a fact that fundamentally distinguishes the current period from Soviet times.

A second potentially problematic feature of this course is the constant demand for the development of “critical thinking,” which does not fit well with the overtly exclusive nature of the theoretical underpinnings offered.

The course is being developed as a “regular” university course, with all the usual elements. One special feature is the use of special platforms, such as the “Russia National Center,” where various events are held as part of the discussion and development of the project.

In the regions, flagship universities have been selected to implement programs for training teachers in their area. For example, St. Petersburg State University is the flagship for the Northwestern Federal District, while North Caucasus Federal University is the flagship for the North Caucasian Federal District. The Znanie Society holds lectures and public events aimed at popularizing the course.

It is worth noting that attempts to develop “specialized national theories” (for example, national political science), although declared, find no support from the Putin administration.

From the beginning, the “Foundations” project was a patchwork of ad hoc texts and did not claim to be a model for or justification of an alternative form of modernization, as did Marxism-Leninism. Even official publications on the practice of teaching the course are full of complaints about the poor coordination between some parts of the course and others.

The ideology of “traditional values,” when applied to higher education and humanitarian and social knowledge, works like a censorship saw, cutting off significant layers of humanitarian and social knowledge, but does not create serious methodological conflicts. Such a project does not and cannot have a common methodological basis.

In the same way, the institutions and practices created to implement this ideological project cannot be compared with the ideological control and monitoring methods of the Soviet era. The systems created make it possible to identify disloyal students and teachers and repress them, yet their structure is not aimed at systemic control and reproduction of ideology. Even teachers of this course privately call the policy of promoting it an “MLM scheme,” thereby demonstrating the specificity of the commercial market approach to ideological control.

* * *

Modern Russian science and higher education are developing according to a hybrid model that combines the Soviet legacy with authoritarian neo-managerialism.

The vertical power structure, ideologization, and control over the content of education are all being strengthened, which reproduces the practices of the late USSR.

Unlike in the USSR, however, the system includes elements of neoliberal governance and allows for variability in one’s relationship to the state, creating room for universities to maneuver.

0 Comments