What goals do sanctions against Russian academia actually achieve?

Dmitry Dubrovsky

Photo: The boycott impacts a small and vulnerable stratum of Russian scientists, namely those who are most critical of Russia’s aggressive policies. Photo by 4C Band on Unsplash

Immediately following the start of the full-scale aggression in Ukraine, various proposals for sanctions against Russian higher education and science appeared and began to spread. These sanctions ranged from partial bans to complete blocks on scientific exchange, access to scientific information, and participation in scientific conferences and publications.

What arguments are used to justify the necessity of these actions? What goals are they trying to achieve with this so-called “academic boycott?” And what goals are they actually achieving?

The Controversy of the Academic Boycott

A quick review of the debates about the meaning of academic boycott reveals that:

- On one hand, in principle, its legitimacy is important from the point of view of academic freedom and knowledge production.

- On the other hand, it is necessary first to establish the responsibility of scientists for what is happening in a particular country.

In order to raise the question of a boycott, there must be some serious crime—a violation of international law or human rights—and it must be established that scientists themselves are responsible for this crime.

The “scientific patriotism” of World War One required scientists to submit unconditionally to the country’s policies. Any other views were punished. At the same time, public support for an aggressive war was perceived as grounds for boycott by scientists from other countries.

Germany. Such was the case with the open letter written by prominent German intellectuals (known as the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three). German science was completely excluded from the global sphere after the Nazis came to power. The basis for the boycott was that German scientists did not resist the active persecution of Jews in German academia, and some even took an active part in it.

USSR. For a long time, the academic boycott of the Soviet Union was significantly limited by minimal academic contact with the West, as well as discussions of the extent to which human rights violations in the country could be grounds for an academic boycott.

The situation changed following the Khrushchev Thaw. Academic and scientific exchanges not only expanded the USSR’s participation in the international global knowledge market, but also made it more vulnerable to academic boycotts. The purpose of such boycotts, initiated by scientists themselves, was to improve the position of scientists in the USSR:

- for example, the boycott against keeping academician Andrei Sakharov in exile

- or the support for Yuri Orlov—more than 200 leading American scientists signed a petition to the USSR Academy of Sciences protesting against his arrest and conviction

South Africa. The boycott of South African universities was related to their direct participation in the apartheid system, as the country’s universities were segregated into “black” and “white.” The main instruments of pressure were

- scientists refusing to travel to or work in South Africa

- scientists from South Africa being denied participation in international conferences and publications

Israel. The basis for the academic boycott in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the alleged responsibility of Israeli academic institutions and the “vast majority of Israeli intellectuals,” who, according to Palestinian activists, either directly support the occupation or “have been complicit through their silence.” One of the founders of the BDS campaign, Omar Barghouti, believes that there is a moral responsibility (“moral obligations of scholars in responding to situations of oppression when carrying out such obligations conflicts with that notion”).

Renowned researcher Martha Nussbaum has criticized this stance, proposing a set of alternatives to a general boycott:

- public reprobation

- public protest campaigns

- protests against public lectures by people involved in violations of academic freedom

Nussbaum sees support for scientists persecuted in one country or another as an alternative to boycott.

Common themes in criticisms of the academic boycott include:

- the injustice of accusing those who are already subject to pressure and persecution in their own country; and

- the lack of connection between the requirements of academic freedom and the demand, by supporters of the academic boycott, that sanctions should be introduced against all scientists, without exception, on the basis of their citizenship.

Academic Boycott and Academic Sanctions after February 2022

A good review of publications discussing the boycott of Russian science since the start of the full-scale war provides a set of arguments that the authors use to justify it.

The set of arguments in favor of an academic boycott is based on the principle of the collective responsibility of Russian science and higher education, which can be divided into several sub-arguments.

The first and main argument is the exceptional nature of the situation, the “state of emergency” in the academic world and the general demand for the world “not to stand aside” and to take part in the boycott. The American scientist Gerson S. Sher states: “any war is a step against science itself,” which “is repelled by any violence.” One author summarizes: “neutrality is inapplicable in this situation…it requires unprecedented reactions from the world scientific community.”

The second argument is the loss of Ukrainian science as a result of the war. The damage caused by the Russian army’s actions includes destroyed universities, as well as dead students and teachers. This in itself calls for a retaliatory measure in the form of an academic boycott. Strictly speaking, this argument is a quid pro quo.

The third argument is motivational (or signaling): Under the pressure of sanctions, Russian citizens in general, including scientists, must stop the war. Thus, the rector of the Norwegian Institute of Science and Technology, commenting on the academic boycott, speaks of it as a peaceful but effective weapon directed against Putin to stop the war.

The fourth argument is moral—an appeal to the shared guilt of Russian scientists. Russian science and higher education are overwhelmingly viewed as supporting the war. This conclusion is based, in particular, on a rather dubious interpretation of sociological surveys and the famous “letter of Russian rectors” in support of the war.

The fifth argument is pragmatic. Russian science is seen as a weapon of war. The militarization of higher education carried out by the Russian regime includes both ideological and technical components. From the point of view of the authors who wrote the most detailed program of academic boycotts of Russian science and higher education, this makes the boycott not only morally justified, but also pragmatic.

Surprisingly, the final common argument concerns violations of academic ethics or academic rights or freedoms by Russian researchers and scientists themselves—for example, the work of nuclear specialists at the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant seized by Russia.

It should be noted that the proposed academic boycott projects say virtually nothing about supporting the basis of academic freedom or dissidents within the country.

Analysis of Arguments and Discussion

From a scientific point of view, the argument about moral responsibility is based on a surprising trust in official Russian polls and surveys, as well as on a strange interpretation of anti-war petitions. Thus, the authors of a scientific article in support of an academic boycott appeal to a number of scientists who signed anti-war petitions. The fact that they are so few in number is considered proof of…the pro-war position of the majority. At the same time, actual military censorship has been active in Russia since March 2022, meaning that signing such letters is grounds for administrative and even criminal prosecution.

Thus, calculations of the percentage of academics who have signed letters of protest against the war (the number of signatories is divided by the total number of researchers and teachers in Russia) appear to be digital manipulations that say nothing about the real attitude toward the war in Russian academia.

Finally, the use of pro-government pollsters as proof of mass support for the war, which supposedly extends equally to scientists, seems like a dubious argument.

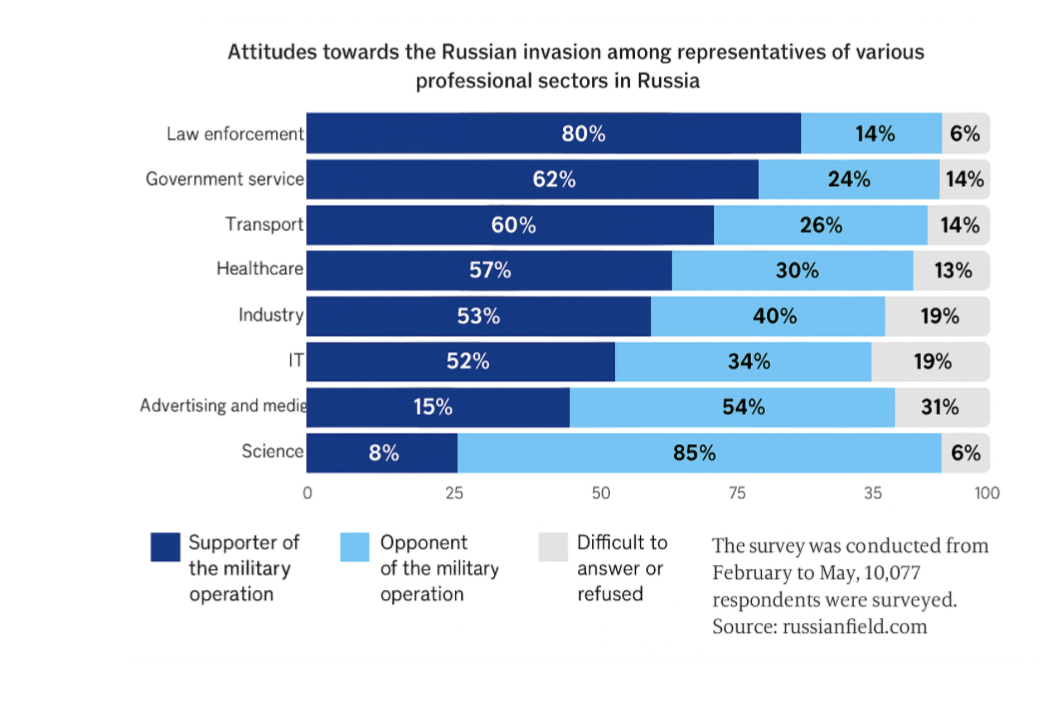

A survey by the independent sociological group Russian Field in the spring of 2022 showed that at that time, it was scientists—more than representatives of any other professional group—who were the most consistent critics of the war.

Source: Russian Field, 2022

The argument citing the pro-war statements of Russian rectors is worthless, since it is based on the idea that they were democratically elected and offer real representation, when in reality this is completely absent in Russia.

Consequences of the Boycott

Not all of the proposed measures concerning academic boycotts have been implemented. Nevertheless, the real consequences are quite tangible.

A recent survey of 1,967 Russian scientists showed not only the scope, but also the depth of these consequences. Three-quarters of Russian scientists have experienced the effects of academic boycotts at least once. Significantly, only the most productive Russian authors were studied: those who regularly published in international scientific journals and worked on international scientific projects.

Consequently, the boycott affects the most internationally active researchers—in the Russian context, those who demonstrate the greatest support for democracy and liberalism.

Conversely, the greatest support for the conservative course comes from those whom the academic boycott cannot actually touch, due to their lack of international experience and international scientific publications.

Thus, this kind of boycott hits precisely the small and vulnerable stratum of Russian scientists included in the system of international exchanges—that is, by common opinion, those most critical of Russia’s aggressive policies.

Finally, the measures initiated by the state, not scientists, not only deprive scientists within Russia of subjectivity, but also deprive national academies in Western countries of the opportunity to protect the principles of academic freedom. Restrictions are introduced on the initiative of governments, not scientists.

Toward a More Subtle Strategy of Academic Boycott

While a complete ban on Russian science and higher education obviously has strong moral support, such actions seem only to help Putin to reinforce the image of a “besieged camp”— thereby bringing Russia closer to China, Iran, and other authoritarian regimes—and to sap support from isolated pockets of resistance within the country.

A more balanced approach might include the following measures:

- The blacklist should include only those institutions whose leadership is completely under the control of state security forces, thereby targeting the true accomplices of repression.

- Tailored support measures—remote teaching platforms, emergency fellowships, and fast-track visas—should be guaranteed for scientists forced to leave the country so they can continue their research.

- Conditional cooperation in conditionally apolitical scientific fields (climatology, public health research) should be permitted on the basis of transparent agreements that protect foreign partners from government interference.

- Permanent monitoring of violations of academic freedom by organizations such as UNESCO or the Council of Europe should be established, with the possibility of adjusting sanctions depending on the situation.

By combining the principled isolation of Kremlin-subordinate institutions with reliable support for oppressed scientists, the international academic community can simultaneously defend both ethical responsibility and the universal right to free research.

Dmitry Dubrovsky holds a PhD in History and is a researcher in the social sciences department at Charles University (Prague), a research fellow at the Center for Independent Sociological Research in the USA (CISRus), a professor at the Free University (Latvia), and an associate member of the Human Rights Council of St. Petersburg.

0 Comments