How scientific and educational cooperation between Finland and Russia has collapsed since February 24.

Gleb Yarovoy

Photo: The war dismantled project consortia, halted cooperation, and, it seems, has become a source of shame for everyone. Author: Jori Samonen, CC BY 2.0

Educated Neighbors Are Good Neighbors

Spring 2016. Crimea is already “ours,” the war in Eastern Ukraine rages on, but it’s still four years before COVID and a full six before Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine. Several colleagues from Russian and Finnish universities—among them the author of this article—write a joint application to the Kone Foundation for a project under the working title “Cherez vysshchee obrazovanie—k dobrososedstvu” (Through Higher Education to Neighborly Relations). Later, the participants agree on a more succinct name: EDUneighbours.

Once upon a time, both universities and the professors working there were members of the Finnish-Russian Cross-Border University, or CBU. For several years, the CBU was financed by the Finnish Ministry of Education. The university united a number of Russian and Finnish higher educational institutions in an academic network that included dual-degree programs and many bilateral collaborations.

Research Focus and Data Collection

Participants in the EDUneighbours project aimed to better understand the role of science and higher education in promoting friendly relations between Finland and Russia.

- The first task was to study the extant dual-degree programs and determine best practices, main problems, and the motivations of student participants.

- The second was to assess the potential impact of scientific and educational cooperation on intergovernmental interactions at various levels, and vice versa.

Project participants cataloged information about dual-degree programs, conducted dozens of interviews with teachers and administrative workers at participating universities in Russia and Finland, and held focus groups with program graduates.

From Academic to Applied Collaboration

My area of focus was Russian universities that collaborated with their neighbors not just on an academic level, but also on a practical level.

It turned out that many higher educational institutions in neighboring areas of Russia and Finland had begun to shift from educational and scientific projects to cross-border collaboration projects. Some of these had an academic component, but many were founded on the logic of the “third mission” of universities, in addition to education and scientific research.

Project consortia for applied projects often included a university (either on the Finnish or Russian side) and several non-academic partners—businesses, NGOs, and both local and regional governing bodies.

Thus, the Cross-Border University and its educational projects were replaced by dozens of transborder collaborative projects. The range of topics was diverse—from developing entrepreneurship to creating a network of bike paths, from new technologies in the IT sphere to waste-sorting.

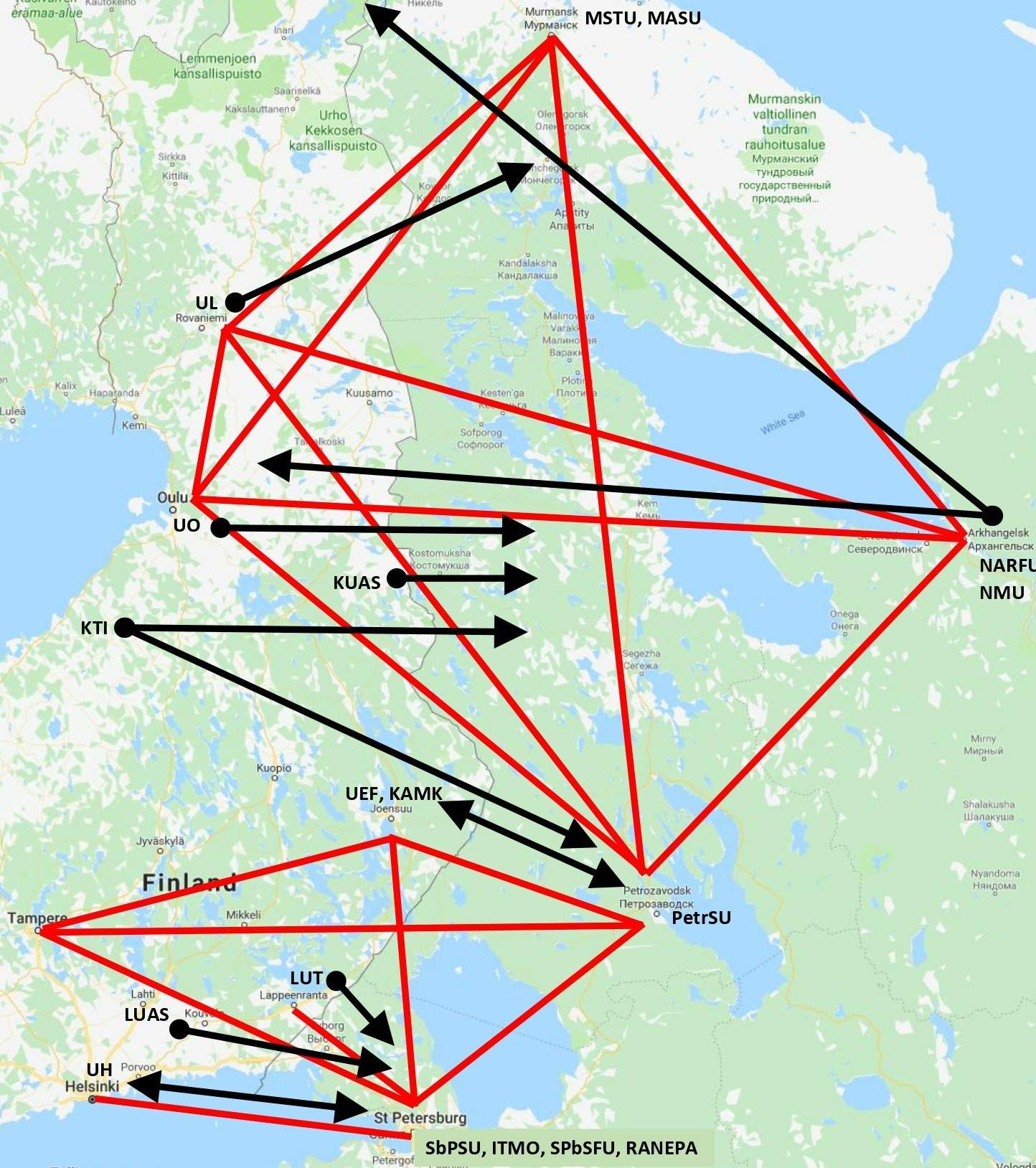

The map shows academic dual-degree programs (red lines, data from 2006-2020) and applied cross-border collaboration projects (black lines, data from 2006-2022) between universities in Finland and Russia. After the start of the war, dozens of projects were frozen and collaboration between universities was terminated.

The trend was exceedingly obvious, but explanations thereof varied widely.

- Some pointed directly to the importance of developing the entrepreneurial capabilities of universities.

- Others said that applied projects made it possible to fulfill KPIs internationally: trips abroad in the form of internships and academic exchange programs were arranged, and the data collected were used for scientific and methodological publications.

- Still others noted that funds from the projects were used to improve university infrastructure, and so on.

Project teams worked effectively, which, to use Vladimir Gelman’s terminology, made it possible to refer to them as “pockets of effectiveness” within many universities in the North-West of Russia. The universities more broadly were no exception to the system of “bad governance” in Russian higher education and science.

Trust and Common Goals before and after February 24

The majority of our respondents—collaborators on applied projects from Russian and Finnish universities—considered it important to talk about trust between project participants. For some, this took years to build. Some quickly found a common language with their new colleagues. Moreover, Russian and Finnish applied researchers were no different from their academic counterparts, who always built their educational and scientific collaborations on a foundation not only of common goals or interests, but also of common values.

After February 24, members of various consortia—both academic and applied—instantly forgot about the trust they had gained over the years and their common values. The war dismantled project consortia, halted cooperation and, it seems, has become a source of shame for everyone.

For the Russians because they are citizens of the warmongering Russia and employees of state institutions.

For the Finns because they are engaging with those who have not openly opposed the war.

Many of those who have remained in Russia (and these are the absolute majority) and who were interviewed in the months following the start of the “special operation” explicitly stated that they felt abandoned, including by foreign colleagues whom they “trusted.”

Scientific, and not simply emotion-fueled, answers to our questions—did this trust exist; why has it vanished; can it be rebuilt; and if so, under what conditions—have yet to be found. This will be an impossible task while the war rages on.

But until we have these answers, we can still concretize several intermediary results of the halt in cooperation.

Apoliticism as a Cause of the Crisis

“Science and education have a positive effect on the relationship between countries but should be separate from politics.” This is how our interviewees—on both the Russian and Finnish sides—viewed the connection between growing Russian authoritarianism and academic cooperation.

EDUneighbours PI Sirke Mäkinen wrote poignantly about this in her article “Nothing to Do with Politics? International Collaboration in Higher Education and Finnish-Russian Relations,” published at the beginning of November 2022 in the European Journal of Higher Education. Dmitry Dubrovsky wrote about the advocates of “pure science” in a recent blog post.

It would be too bold to assert that the massive “politicization” of scientists could influence the foreign policy of governments. However, both the history of the USSR/Russia and the histories of other countries (Finland being no exception) suggest that it would be wrong to underestimate scientists’ influence on the political class.

Political Geography

The refusal of Finnish, as well as most European, universities to collaborate with Russian universities and colleagues that have Russian institutional ties is a clear signal to Russia: we can forget about scientific or educational cooperation with Europe for years, if not decades, to come.

This means that we will have to focus our cooperative efforts on colleagues in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. Our respondents say that such a turn is taking place very actively even in small regional universities: some are offered academic exchanges with Tajikistan, some are conducting scientific projects with Zimbabwe, some will have to establish institutional interactions with China.

It seems that China has become the most popular option among Russian universities:

- China has the money to develop joint scientific and educational initiatives

- In the past decade, China has actively internationalized its sciences and advanced cooperation with Western scientists to a qualitatively new level.

It appears that under conditions of limited access to the West’s scientific achievements, the Russian Ministry of Education will want to use the scientific triangle between the West, China, and Russia to its advantage. The Nordic countries, including Finland, have become important, if not key, players in cooperation with China in certain disciplines, such as various areas of Arctic research.

In the guidelines for academic cooperation with China published at the end of March 2022, the Finnish Ministry of Education explicitly acknowledges that:

“academic cooperation with China is more important than ever” because “it is beneficial for Finnish academic institutions and the society in general…despite differences in…values” [emphasis mine –G.Y.]

One hopes that Finnish scientists will carefully consider not only the opportunities, but also the risks referred to in these recommendations, and will be able to avoid not-always-appropriate apoliticism in cooperation with their Chinese colleagues.

“Uneducated Strangers”

Fall 2022. Crimea is still “ours” for now, COVID is remembered as nothing more than a fun little adventure, and the war in Ukraine has taken tens of thousands of lives, destroyed the economies of the two countries, and severed social ties.

The Cross-Border University is long gone. All the projects and consortiums that worked “on trust” until February 24, 2022, have been frozen or dissolved.

The Russian sciences will be thrown back decades. New generations of Russian scientists are likely to be seen by their Finnish colleagues less as “educated friends” and more as “uneducated strangers.”

Disclaimer: This article reflects the personal opinions of the author; these may differ from the views of other participants in the EDUneighbours project.

0 Comments