7 Topical Titles That Will Captivate More than Just Specialists

Andrei Gerasimov

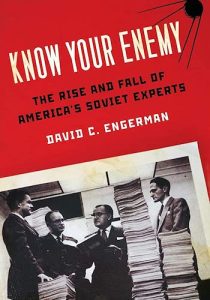

Photo: Any study of society exists within the society itself. Photo by Maria Teneva on Unsplash

Science and technology studies, or STS, has long been part of mainstream public intellectual life. Stars in the field, such as Bruno Latour and Annemarie Mol, are cited regularly.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about the social sciences and humanities, or SSH. For many years, they were not formalized in a common interdisciplinary space.

Fortunately, in recent years, historians and sociologists interested in unearthing the social foundation of their own sciences have begun to actively reach out to one another, holding joint conferences and publishing journals.

This may seem like a subject that would interest only a select group of geeks and specialists. But this is not the case.

The mission of the social and humanitarian sciences is not simply to satisfy a fascination with museum rarities or antiques, but to help colleagues acquire a reflective attitude toward their own practices and institutions.

First and foremost, reflection means the realization that any study of society exists within the society itself. For example, one of the prerequisites for the existence of the social sciences and humanities is academic freedom, which didn’t simply fall from heaven, but was hard won by scientists living within specific social conditions. The study of these conditions does not undermine the value of those freedoms, but, on the contrary, helps us better understand the context of their existence.

I suggest getting acquainted with some books that have already entered the canon, as well as new works in the genre of social sciences and humanities, the conclusions of which may be of interest to many. These books cover a wide range of topics, concepts, and techniques. They help to evaluate an actively developing area of knowledge, making it easier for people with a wide variety of backgrounds to get to grips with this issue.

Fritz Ringer, The Decline of the German Mandarins: The Academic Community in Germany, 1890-1933

(Moscow: NLO, 2008 [1969]).

Published in 1969, Fritz Ringer’s classic work set the highest standard for research in the social sciences and humanities.

The German historian presents us with the tragedy of the highest stratum of German academia. Having initially competed with the church in the field of education, university professors eventually became a closed class, championing ultra-conservative ideas like cultural superiority over neighboring nations and aggressive militarism. Even the youngest and most progressive Mandarins, according to Ringer, were not free from the illusions and prejudices of an era full of political and military disasters.

The Decline of the German Mandarins should be considered a warning to any professional corporation that has become dependent on an authoritarian regime. Then again, these warnings often go unheeded.

Pierre Bourdieu, Homo Academicus

(Moscow: Gaidar Institute Publishing House, 2018 [1984]).

Bourdieu’s structuralist sociology has been criticized for its emphasis on statics and neglect of dynamics. If this is a fair criticism, it certainly does not apply to this book, which provides a vivid picture of the evolution of the French university system during the post-war decades.

Bourdieu attempts to convey the seething spirit of academia on the eve of the events of 1968 and to provide a rational explanation for what happened. He believes we must consider a variety of inter-university processes:

- demographic pressure from the large post-war generation

- solidification of patronage ties around influential professors

- the struggle of new humanitarian disciplines for prestige and recognition, etc.

At the same time, it is fundamentally impossible to identify the single most important driver of change. All significant factors were part of one social whole: the academic field. It is here that the epistemic—that relating directly to knowledge—melds with the social, the intellectual with the political.

These are simple truths that both jealous “science-outside-of-politics” purists and partisan activists who deny the value of rational university-wide discussion would do well to recall.

Mikhail Sokolov, Katerina Guba, Tatyana Zimenkova, Maria Safonova, and Sofia Chuikina, How to Become Professors: Academic Careers, Markets and Power in Five Countries

(Moscow: NLO, 2015).

This collective monograph by Russian sociologists examines the structure of sociology in four academic superpowers—Britain, Germany, the USA, and France—as well as Russia.

One of the goals of the book is to acquaint young Russian scientists with the ins and outs of obtaining a degree, hiring processes, and moving up the career ladder in Western educational systems. The team of St. Petersburg sociologists likely did not even know how relevant this issue would be within a few years of the book’s publication.

No less fascinating is the chapter on the Russian version of sociology, with which we are better acquainted. Some may criticize the authors for their sample size, which is limited to the sociological community of St. Petersburg. However, in their thinking, it is in a microcosm such as this that we can see the entire history of sociology in our country over the past several decades.

Perhaps their research will pay off.

Donald MacKenzie, An Engine, Not a Camera: How Financial Models Shape Markets

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006).

Donald Mackenzie, one of the preeminent voices of the Edinburgh School of Science, is tired of dealing with traditional STS topics such as rivalries between schools of statistics or the development of rocket engineering.

The Scottish sociologist has instead turned his attention to the most prestigious of the social sciences: economics. His book is a collection of studies on performativity—the phenomenon of institutions manifesting the scientific concepts on which they were built into reality. While other researchers often try to find traces of the influence of external social forces on science, Mackenzie shows how science itself can push back on society.

The author’s empirical subject of choice is the development of economic theories since the beginning of the 1960s. The author explores how formal models have been applied in the design of private marketplaces and government oversight bodies.

In the words of one of the classics of sociology, “only an idea that has gripped the masses becomes a material force.” And what material force today is more powerful than capital?

David C. Engerman, Know Your Enemy: The Rise and Fall of America’s Soviet Experts

(Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Today, the word “Sovietology” has become almost a curse word. The term has become associated with those who draw far-reaching conclusions about the Russian political class from where guests are sitting at the Victory Day parade.

Once upon a time, Sovietology was an entire academic industry in the United States. The most influential overseas elites heeded its findings.

David Engerman tells the real story of Sovietology, which was full of conflict between political scientists and historians, military experts and political party consultants. A return to the realities of the Cold War in international politics is unlikely to revive the entire discipline of Sovietology, but some of its practices may return. Engerman’s research will help evaluate what the choice will consist of.

David Mills, Difficult Folk? A Political History of Social Anthropology

(New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2008).

Discourse about anthropology as a colonial science is a longstanding item on the academic agenda. But to what extent was this science embedded in the imperial order?

Anthropologist David Mills offers one answer to this question. His focus is not so much on ideas and people as on the organizational structure: faculties and departments, professional associations, informal networks, scientific foundations and public services.

Mills shows how, at the intersection of bureaucratic and collegiate institutions, a community full of contradictions emerges. British scientists

- enjoyed the patronage of the administrations of the colonial territories, but defended the freedom of the conquered peoples

- constructed generalizing theories but satisfied the demand for “field expertise” on legal matters and issues of language.

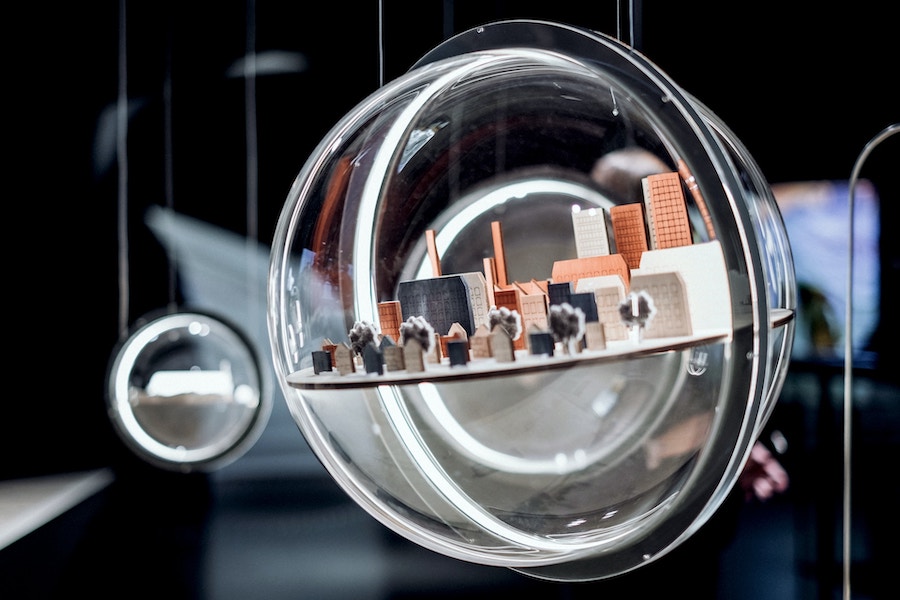

Monika Krause, Model Cases: On Canonical Research Objects and Sites

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021).

Monika Krause’s monograph is dedicated to an unusual research object…research objects themselves. The German sociologist is interested in what she calls model cases—the predominant and favored objects of study across different disciplines.

The classic model case for biology is the Drosophila fly. The humanities and social sciences have a whole variety of model cases. In literary criticism, it is the tragedies of Shakespeare, while for economic history, it is early European capitalism, and so on. Krause is interested in how researchers access especially important research objects (for example, a historian may read source materials in archives), how reliable and accessible the objects themselves are, and in what setting—or environment—the research takes place.

Along the way, the author offers an original explanation of inequality in the global scientific division of labor. The US and Western European countries do more than just set the tone for concepts and methods; they are the repository of model cases. For example, the archives of the French Revolution are kept in Paris, while the urban planning blueprints from the period of rapid industrialization at the turn of the twentieth century are preserved in Chicago. Whoever owns the research objects holds the key to the entire discipline.

0 Comments