How the Kremlin’s politics are aggravating the crisis facing those scientists who remain in Russia.

Dmitry Rudenkin

Photo: The atmosphere of freedom required for effective scientific work is dissipating in Russian universities. Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

When discussing future scientific breakthroughs, the Russian authorities are pursuing policies that significantly limit the capabilities of scientists and make the free development of science almost impossible.

A “Brighter Future”

Following the start of the war in Ukraine, the bright future of science became a favorite discussion topic among Russian politicians. Vladimir Putin loves to demonstrate his faith in the potential of Russian science: he talks constantly about the importance of new scientific projects, sets ambitious goals for scientists, and expresses confidence in future discoveries.

This rhetoric has also been adopted by other speakers, who regularly talk either about the stability of Russian science in the face of external challenges or about forthcoming world-class developments. Their statements make it seem as though Russian science is on the threshold of one of the best periods in its history.

The reason for this ostentatious optimism is clear. Putin’s reckless decision to invade Ukraine has cost Russian science dearly. The world’s negative reaction to the outbreak of war has forced Russian scientists to endure limited international relations, the inaccessibility of critical resources, and the migration of thousands of qualified specialists.

Russian politicians’ hopeful statements about the bright future of science are a natural attempt to pretend that the consequences of these difficulties are not as catastrophic as they seem.

The problem is that the idyllic picture reflected in such statements does not correlate with the actual depth of the crisis in which Russian science has found itself over the past year and a half. The issue is not simply that the protracted war and international sanctions have created many unprecedented difficulties. A much bigger problem is the ill-conceived policy of the Russian authorities, which not only has not helped to overcome these difficulties, but has even created new ones.

“Unfriendly” Science

The longer the war goes on, the more persistently the Kremlin divides the world into “friends” and “enemies.” The current policy of the Russian authorities is based on an official list of so-called “unfriendly states.” It includes dozens of countries that provide assistance to Ukraine and/or have imposed sanctions against Russia.

The rhetoric used by the Russian authorities about these countries is extremely aggressive. Cooperation with them is kept to a minimum.

The Kremlin’s isolationist policy has changed Russian scientific institutions’ approach to international cooperation. University leaders, who are receptive to the statements made by Kremlin officials, have begun to suppress contacts between their subordinates and their colleagues from “unfriendly states.”

Typically, these restrictions are strictly informal. But there have been cases where they have been regulated by official order of the rector.

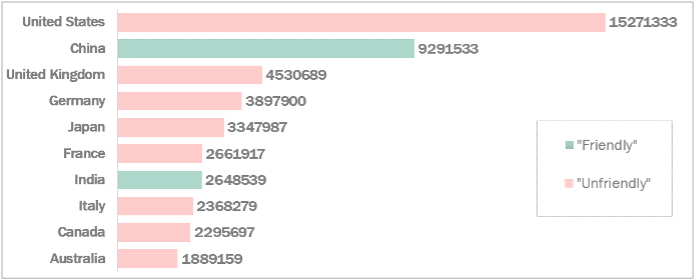

The nuance here is that the Russian list of “unfriendly states” includes almost all those countries that play the most prominent roles in the development of world science. In particular, the list includes:

- all of the top 10 countries in the Global Innovation Index,

- 9 of the top 10 countries in the AD World Country Rankings, and

- 8 of the top 10 countries in the Scimago Journal & Country Rank.

In other words, limiting cooperation with scientists from “unfriendly states” is tantamount to declaring a moratorium on interacting with the key drivers of world science.

Figure 1. Top 10 countries in the Scimago Journal & Country Rank (by total number of articles published, 1996-2022) and their status as “friendly” or “unfriendly” to Russia

Source: Scimago Journal & Country Rank

The price of this moratorium is the increasing international isolation of Russian science.

Now, this isolation is relative: the academic communities of many “unfriendly states” have suspended cooperation with Russian scientific institutions but are still prepared to deal with specific specialists. By aligning themselves with the Kremlin’s aggressive rhetoric and suppressing contacts between their employees and colleagues from “unfriendly states,” Russian universities risk destroying such cooperation and turning relative isolation into absolute isolation.

Ban on Truth

The severe consequences of the war and international sanctions have forced the Russian authorities to seek out convincing ideological arguments that might reconcile society to the costs of the new geopolitical reality.

It seems that this problem has been solved by artificially adding sacred meaning to the confrontation. By the spring of 2022, Russian propaganda had already begun to depict the conflict with Ukraine as an episode in a holy war between Russia and the powerful “collective West.”

The “Special Path.” As a consequence of this policy, the state began intervening in non-core social science issues. Speculating on the theme of confrontation with the “collective West,” the Russian authorities began to adopt official documents declaring Russia’s “special path” and its features.

As a result, official interpretations of concepts devoid of any stable scientific interpretation—among them “traditional values,” “historical truth,” and “Russophobia”— began to appear in Russian official documents. Free analysis of the relevant issues has become impossible: one must either rely on the “correct” official interpretations or accept the risk of being accused of breaking the law.

“Foreign Phenomena.” The more aggressive the Kremlin’s anti-Western rhetoric becomes, the longer becomes the list of social phenomena that Russian ideologists declare foreign to Russia’s “special path.” The cultivation of social contempt for these phenomena creates a taboo around studying them.

Probably the main victim of this taboo has been research in the field of LGBT issues, which has been almost impossible since the adoption of the scandalous law banning so-called “LGBT propaganda.” But difficulties also arise when exploring other issues that conflict with the logic of the “special Russian path”:

The consequences may be more dire than they seem. The unceremonious interference of the Russian authorities in methodological issues of social science indicates that their attitude toward science is increasingly gravitating toward cynical political utilitarianism. The scientific validity of research is coming to interest them less than the relevance of this research to immediate political objectives.

Although this feature of public policy has to date affected only the social sciences, this apparent circumscription is deceptive. If policymakers accept that it is possible to intervene in internal scientific debates, they will be willing to do so whenever they deem it necessary.

Lost Freedom

Faced with society’s negative reaction to the outbreak of war, the Russian leadership began to take measures aimed at suppressing anti-war sentiment.

- One of these is the adoption of laws imposing criminal liability for public anti-war speeches.

- Another is the growth of ideological pressure on the work of educational and cultural institutions that influence the formation of public opinion. The Kremlin openly began to use these institutions for pro-war propaganda.

The result of this policy has been a dramatic change in the daily life of hundreds of universities, which are the main venue for Russian scientific research. The familiar realities of their lives have become

- demonstrations in support of the war

- military lectures

- fundraising for the army

- teaching ideologically driven educational courses

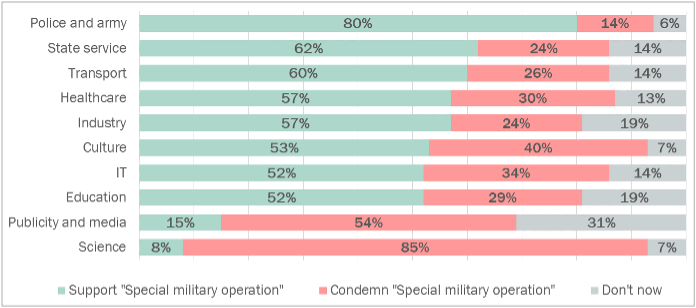

Universities are being cleansed of disloyal specialists. Back in the summer of 2022, Russian authorities were already expressing concern about heightened anti-war sentiment in the academic community. These sentiments were visible both in sociological surveys and in the famous “petition of scientists.”

Calls to stop collaborating with “unpatriotic” scientists and teachers quickly turned into a large-scale campaign of dismissals. We now know of dozens of specialists who lost their jobs shortly after making anti-war statements.

This sent a message to university employees: showing disloyalty could lead to problems.

Figure 2. Attitudes toward the start of the war against Ukraine among representatives of various professional communities in Russia (February-May 2022, N = 10077)

Source: The Insider

The cost of these changes in the life of universities is the slow extinction of academic freedom. By turning universities into weapons of pro-war propaganda, Russian authorities have imbued their everyday life with militaristic narratives and made it taboo to express disloyal views.

The resulting atmosphere of resignation demoralizes Russian scientists, forcing them to exercise maximum caution in making any statements. The atmosphere of freedom necessary for effective scientific work is vanishing from Russian universities.

* * *

It is clearly too early to talk about the death of Russian science. But its current circumstances increasingly resemble some kind of barbaric social experiment.

The Russian scientific community has been weakened by the heavy impact of international sanctions, interrupted interstate cooperation, the massive exodus of qualified specialists, and other problems that have arisen since Russia’s attack on Ukraine. The Kremlin’s policy not only has not helped to solve these problems, but has even created new ones.

A scientist who continues to work in Russia is forced to endure

- an actual ban on cooperation with colleagues from key global scientific powers

- severe restrictions on academic freedom

- the authorities’ willingness to apply crude ideological pressure to research practices

Under these conditions, any successful development of science can be considered a miracle.

If the people who rule Russia believe that such miracles are possible, then it can safely be said that they simply do not realize the real consequences of their own decisions.

0 Comments