Russian universities and research institutes see the resurgence of Soviet practices of state control over science and education.

Dmitry Dubrovsky

Photo: The roof of the Russian Academy of Sciences. (Marcella Bona, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, bit.ly/2wh7kBd)

In its new section, Academic Freedoms, the Center for Independent Social Research will regularly—once a fortnight—tell the most relevant stories concerning the academic community. Today, we open this section by discussing general trends.

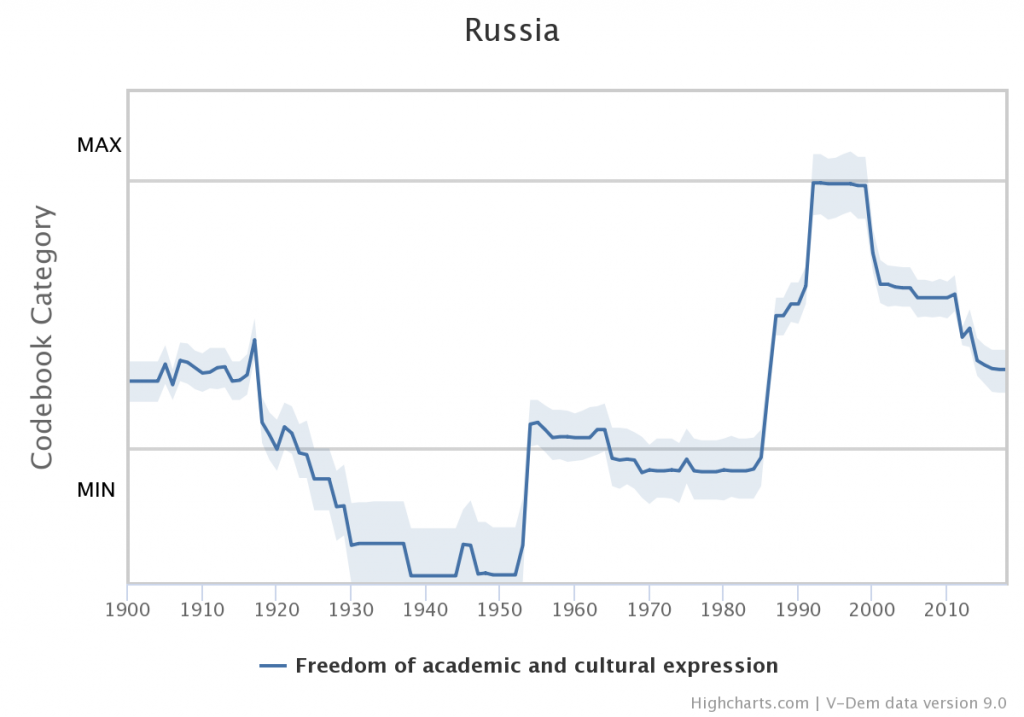

The path that Russian science has traveled since the 1990s demonstrates a downward trajectory in terms of academic rights and freedoms.

Thirty years ago, the academic community of the new Russia served, in many ways, as both the creator and the beneficiary of freedom from the ideological diktat and state censorship of the Soviet era. The work of a scientist or academic, especially in the humanities, relies on having a certain level of ideological freedom. It is for this reason that the academic community has turned out to be one of the main beneficiaries of free speech.

Freedom of academic and cultural self-expression, Russia, 1900-2019 (Graph: Democracy index V-dem, bit.ly/39v1kDa)

Today, in a context where free speech is ever more curtailed, academic freedom in Russia is also increasingly limited. Let me list the main trends.

SPY SCARES. A wave of spy scares that emerged in Russia at the beginning of the 21st century directly affected research workers and academics. Two professors at Baltic State Technical University—Yevgeni Afanasyev and Svyatoslav Bobyshev—were convicted of “espionage in favor of China.” Currently under investigation is 75-year-old Viktor Kudryavtsev, an officer of the Central Research Institute for General Machine Building who is charged with the alleged provision of classified data to the Belgian Von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics.

Law enforcement officials’ loose interpretation of the concept of “state secrets” puts researchers participating in international projects in a very vulnerable position.

The situation is aggravated by the closed nature of the trials, which feature flagrant violations of the principles of judicial procedure. This was highlighted by the human rights lawyers of Team 29 in their report The Complete History of High Treason and Espionage in Contemporary Russia.

The special services are interested in fabricating “espionage” cases and backing them up using “experts” from their own ranks. This makes it almost impossible for scientists accused of treason or divulging state secrets to get themselves acquitted.

Experts from Team 29 also associate the increase in the number of espionage trials with the intensification of the activities of the so-called First Departments (also called security departments) in educational and research institutions. The First Departments were created during the Soviet era to oversee scientists who worked with military or dual-use technologies. They were famous for imposing exceedingly heavy restrictions on scientists, such as bans on travel abroad and scientific publications.

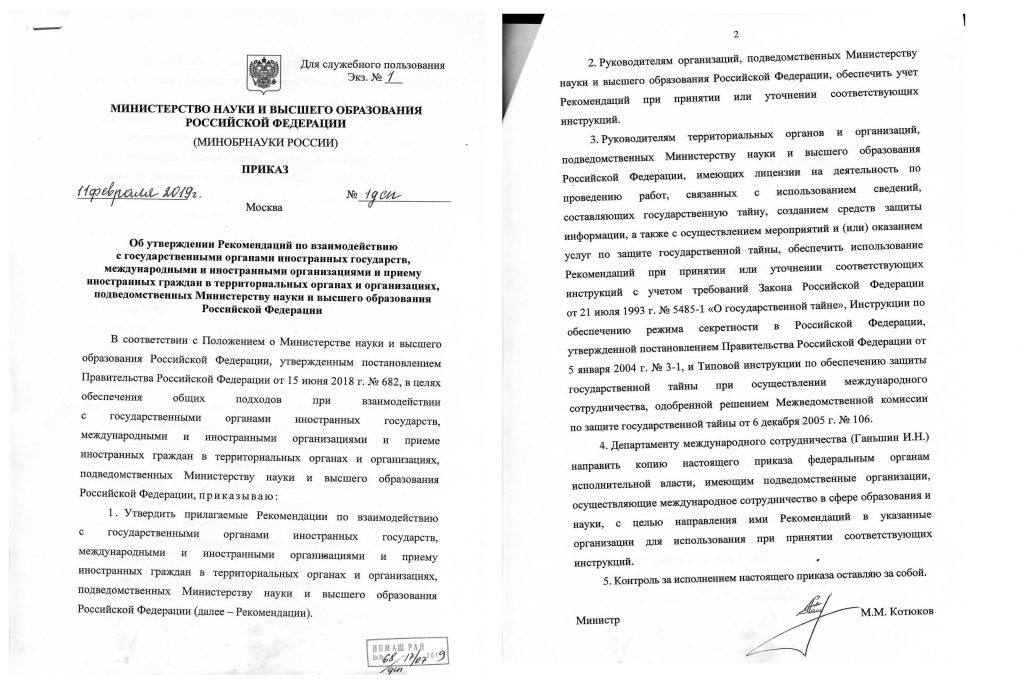

CONTROL OVER FOREIGNERS. The Soviet practice of “control over foreigners” has been revived, in particular concerning contacts between the personnel of scientific organizations and their colleagues from abroad. In February 2019, the Minister of Science and Higher Education of Russia, Mikhail Kotyukov, signed recommendations tightening the rules for communication with foreign colleagues. These recommendations reintroduced numerous archaic prohibitions, such as a ban on foreigners possessing the “technical means of processing and accumulating information.”

Order of February 11, 2019 “On approving recommendations for interaction with state bodies of foreign states, international and foreign organizations and reception of foreign citizens […]” (Image: Troyitsky Variant, bit.ly/31Srxcd)

The order catalyzed a wave of indignation and protest among scientists, and a few months later the ministry itself “suggested that research workers disregard the order.” Exactly one year later—on February 10, 2020—the new Minister of Science, Valery Falkov, finally revoked the absurd regulation. However, the fact that it ever existed in the first place is vivid proof of the resurgence of Soviet control practices.

FOREIGN AGENTS. The passage of the laws known as the Foreign Agents Act (2012) and the Undesirable Entities Act (2015) had a profound effect on academic rights and freedoms in the social sciences. Those primarily affected were non-governmental research organizations engaged in empirical research.

The most notorious case has been that of the Levada Center—arguably the only pollster and public opinion research center in Russia that has retained a reputation for being an independent entity.

According to the Russian Ministry of Justice, among the scientific organizations performing the functions of a foreign agent are:

- Center for Independent Social Research (St. Petersburg)

- Center for Gender Studies (Saratov)

- Research and Information Center “Memorial” (St. Petersburg).

Tellingly, the clause of the Foreign Agents Act that explicitly excludes scientific research from the consideration of law enforcement officers has had no practical effect.

PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES. The state policy of licensing non-state universities is changing. The cases of the European University in St. Petersburg and the Moscow Higher School of Social and Economic Sciences (known as Shaninka) are illustrative. Both universities are leaders in Russian liberal arts education and enjoy respect within the international scientific community.

The crisis in the relationship between the state and the European University began with a verification procedure carried out by Rosobrnadzor experts. As a result, the university’s accreditation was revoked, as was its license to conduct educational activities. No less unexpectedly, Shaninka’s accreditation was also revoked. Although both universities eventually managed to overcome the difficulties that arose, the threat of license revocation persists today.

POLITICIZATION OF HISTORY. Official historical policy occupies a special place in the “conservative turn.” According to the historian Ivan Kurilla, history is once again becoming an instrument of state propaganda.

Important milestones in the politicization of history include the establishment in 2009 of a Commission under the President of the Russian Federation to counter attempts to falsify history to the detriment of Russia’s interests and the adoption in 2014 of a federal law aimed at “counteracting attempts to encroach on historical memory regarding events that took place during the Second World War.”

In the current legal context, any attempt to question the official version of the events of World War II may open a researcher up to liability—including criminal prosecution. Vivid examples of such measures are the resignation of the director of the State Archives, Sergei Mironenko, who debunked the myth of Panfilov’s 28 Guardsmen, and the interest of the prosecutor’s office in historian Kirill Aleksandrov’s doctoral dissertation on General Vlasov and the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia. (Aleksandrov’s research was deemed extremist by the St. Petersburg City Court.)

While such cases are not widespread, they nevertheless have a serious impact on the climate in the academic community, making it difficult to work on some topics.

CIVIL ACTIVITY. Increasingly, the civic and political activity of academics and scientists, primarily their public criticism of state policy, has caused them to be persecuted by the state. Two examples include:

- The protracted prosecution of Yuri Pivovarov, director of the Institute of Scientific Information for Social Sciences of the Russian Academy of Sciences, which experts attribute to his “studies of the political system of Russia and numerous public speeches”; and

- The dismissal of MGIMO professor Andrey Zubov for making statements about Ukraine and Crimea that “contravene Russia’s foreign policy.”

Formally, dismissals can be explained by violations of labor discipline, as in the case of Oleg Klyuenkov, a lecturer at Lomonosov Northern (Arctic) Federal University who spoke up about violations of LGBT rights.

More often, however, “troublemakers” on a faculty are dismissed by not renewing their employment contracts, frequently on the pretext that the institution would be unable to provide them with a sufficient workload in the coming year. Two individuals fired in this way were:

- Anna Alimpieva from Baltic State University, who had previously been accused of excessive tolerance of LGBT individuals, criticizing the authorities, and promoting Kaliningrad separatism;

- Alexander Panchenko, a well-known Russian religious scholar from St. Petersburg State University who expressed an opinion in court that contradicted the evidence presented by the “official” expert.

Along similar lines, HSE lecturer and renowned political scientist Alexander Kynev resigned from HSE after the merger of the Department of Political Science of the Faculty of Social Sciences, where he worked, with the Department of State and Municipal Administration.

The list goes on.

* * *

The conservative turn—which, in the Russian context, primarily takes the form of an anti-Western project—increases ideological pressure on science, limits the freedom of teaching and teachers, and (in combination with spy mania) has begun to directly affect the state of academic rights and freedoms in Russia.

The further strengthening of this trend will inevitably weaken the position of Russian science and education abroad. Both the quality and international reputation of Russian science and education will suffer from the restriction of academic freedom.

This is why we are opening a new column on Academic Freedoms. We will follow the field and report twice a month about the most important trends in academic communities.

0 Comments