In February, the Russian State Duma will—on second reading—consider amendments to the Law on Education restricting educational activities and international contacts.

Dmitry Dubrovsky

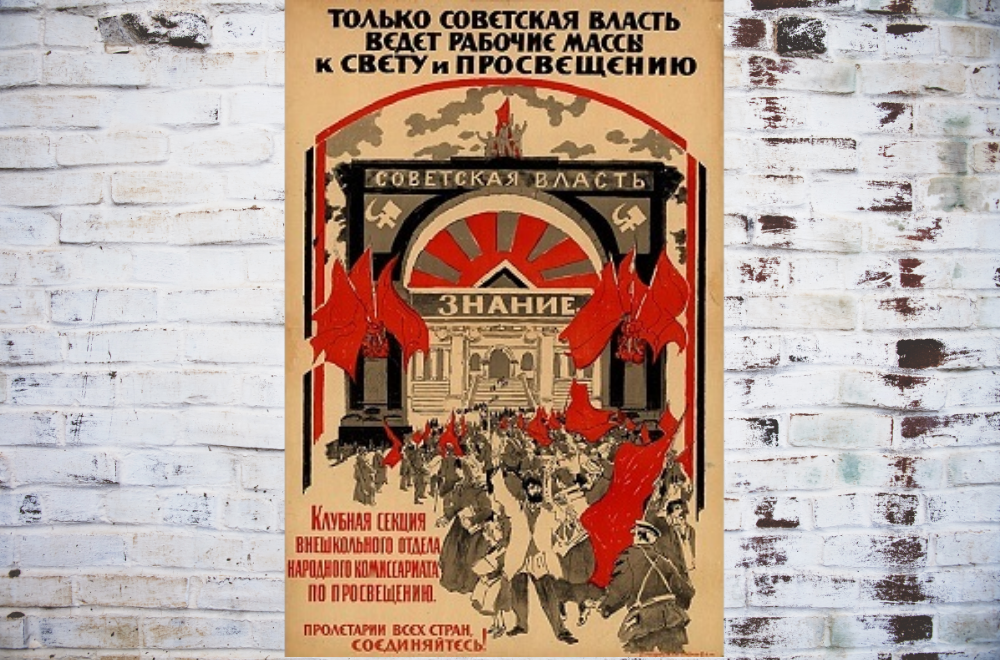

Poster: Unknown artist. 1919, Petrograd, 2nd State Lithograph. (Wikimedia Commons)

In particular, the lawmakers propose introducing a permissive procedure for international cooperation in the sphere of education and for the licensing of educational projects.

The amendments were adopted on first reading in late 2020. During the second phase, they might change considerably. However, the odds of that are slim.

An Anti-Western Package

Changes to the Federal Law on Education of the Russian Federation are part of a package of legislative amendments introduced by the State Duma in December. The same package also includes amendments to the Law on Foreign Agents.

The amendments were the result of the active work of two commissions set up to investigate alleged Western interference in Russia’s internal politics: the Ad Hoc Commission on Protecting State Sovereignty and Preventing Interference in the Domestic Affairs of the Russian Federation and the Commission of the State Duma on the Investigation of Foreign Interference in Russia’s Internal Affairs.

These commissions mimic the name of a U.S. Congressional commission: the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Target Audience—Students and the Academic Community

In its 2020 work report, the Federation Council commission indicated that “youth, students, and academia” are considered to be the United States’ main target audiences in Russia.

According to the authors of the report, Russian “academic structures” themselves allow this interference into Russia’s internal affairs in the interests of the State Department and the Pentagon.

Graduates of the School of Local Self-Government are among those suspected of “contributing” to the implementation of alleged U.S. plans to interfere in Russia’s internal affairs.

Thus, the report made it clear that measures should be taken to limit and control students, “academic circles,” and forms of education not currently subject to state control.

To this end, the State Duma has introduced, among others, a bill aimed at protecting young people and students from the influence of the West.

Mandatory Registration

In an explanatory note on the draft, the authors complain about the lack of regulation of educational activities. Such gaps are allegedly exploited to allow for a “broad spectrum of propaganda activities, including those supported from abroad and directed at discrediting Russia’s public policy, revising its history, and undermining the constitutional order.”

To prevent such “interference,” the law requires the formal registration of any education and training activities (including, for example, the newly established Free University). The project proposes to give the Ministry of Education and Science the right to issue licenses for educational projects.

What Counts as “Educational Activities”?

The term “educational activities” is interpreted very broadly. It may include research projects, lectures, websites, YouTube channels… The bill attacks not only well-known independent educational projects and educational activities conducted by NGOs, but also the activities of universities.

At the same time, special attention is paid to international cooperation. Under the new law, all international cooperation and exchange programs must be approved by a special government body. This will lead to additional political control over universities, further censorship, and more restrictions.

The Benefits of Broad Interpretation

The author of the draft, Senator Andrei Klimov (who is also the chairman of the Commission for the Protection of Sovereignty), openly admitted that the vague definition of “educational activity”—which allows for broad interpretation—is intentional. According to Klimov, “transparent measures” are insufficient in the fight against “dangerous activities.”

The senator argues that those who oppose the new amendments are actually backed by “external forces” and “influenced by Washington.”

According to critics, however, the amendments represent another attempt to empower the state and equip government officials with arbitrary means to silence their opponents.

Precursors

Attempts to “protect” the academic community and students from “smoldering influence” and take control of relations with foreigners already have a history.

- In 2019, the Ministry of Education and Science issued an order obliging academics to obtain their university’s consent to meet with foreign colleagues (the decree was revoked after it met with indignation from scientists and the new minister).

- Similar language was used in the demand of the Nikulinskaya Inter-District Attorney’s Office in Moscow, which included, in particular, a requirement to search for “pro-American groups of influence” in Russian universities. It, too, was withdrawn.

Will the new bill be rejected?

Scientists Are Opposed

The Russian scientific community quickly responded to the challenge. Academics sounded the alarm about the radical legislative amendments, rightfully fearing that they might hurt international cooperation. An open letter by some of those opposed to the amendments was published in the most popular academic newspaper, “Troitsky Variant.” Scientists and science popularizers also said that they would not follow the requirements of the law if it was adopted in its current form.

The “First of July” Club, an informal association of Russian Academy of Sciences academics, likewise protested, arguing that the proposed licensing impedes the constitutional freedom to search for and obtain information. There is a high risk, they indicated, that the process will be carried out selectively, which will strengthen ideological control over the humanities and social sciences, especially history. Moreover, they fear that the amended law will hamper the development of Russian science.

“The atmosphere of suspicion towards scientists and their international contacts stands in stark contrast to Russia’s official goals of internationalizing higher education,” commented Katarzyna (Kasia) Kaczmarska, professor of politics and international relations at the University of Edinburgh. According to Professor Kaczmarska, amending existing rules “further suppresses free exchange of opinions in academic circles” and is likely to “exacerbate scientists’ and researchers’ self-censorship.”

* * *

The state is sending another message to scientists and the academic community: you are not trusted, your international contacts are treated with suspicion. We can expect that scientists will choose research topics and themes for public statements even more carefully. Self-censorship may intensify. According to critics, the result will be increased ideological control over academia.

The growing suspicion about the international contacts of Russian scientists hinders the policy of internationalization of Russian universities, improving their international ratings and attracting foreign students and faculty.

Indeed, the amendments to the law on education have precisely the opposite goal: to eradicate what a group of legislators call “negative foreign interference.” As a result, international educational projects will become even more complicated and risky to carry out.

0 Comments