The shift in the political agenda has heavily influenced the scientific agenda.

Mikhail Sokolov

Photo: We compare the frequency of use of certain terms in the titles, keywords, and abstracts of Russian social science journals. Photo by Leo on Unsplash

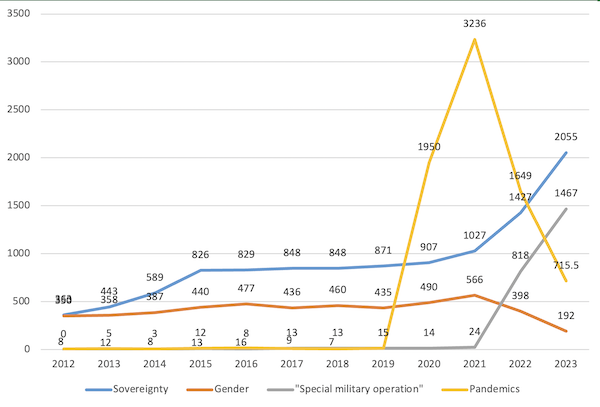

Have the recent shifts in the government’s ideological agenda affected Russian social scientists? Changes in the popularity of the terms “pandemic,” “special military operation,” “sovereignty,” and “gender” indicate that they have.

Arguments “for” and “against”

There are several reasons why these changes might have affected social scientists—and several reasons why they might not.

“For”: The Russian government—and it is no exception in this—demands that its scientists make themselves “useful” by contributing to the country’s economic growth, public safety, and so on.

When government officials proclaim that an issue is “important,” scientists may sincerely strive to be part of the solution—or seek to make it look like the research they are conducting may lead to a solution. Millions of scientists around the world run through the list of “official issues” in their minds when sitting down to write the “Practical Applications” section of their grant proposals.

Following this line of reasoning, it is safe to assume that the launch of the “special military operation” encouraged Russian researchers to study topics related to this subject, or at least to seize the opportunity to pretend that they are doing so.

“Against”: On the other hand, some researchers may be so unsympathetic to Russian state policy that they will not take advantage of their chance to appear useful.

The ratio of sympathizers to non-sympathizers among Russian academic circles is a subject of both heated and completely futile debate, since it seems impossible to conduct anonymous surveys with representative samples of scientists.

However, even those who “sympathize with the agenda” may not be enthusiastic about it.

First, most have their own research programs, imposing considerable inertia on their intellectual trajectories. If they were to suddenly switch to a “hot” research topic, then they would have to abandon almost all the work they had done on their previous topic of study. The very thought evokes a visceral horror in most researchers.

Second, many scientists may be almost as horrified and disgusted by the idea that external factors might dictate the topics, let alone the hypotheses and conclusions, of their research.

A recent study of historians, for example, demonstrated a widespread reluctance to condone the spread of “historical myths” in the interests of the state—even among those who sympathize with state policy. This remains true even though they have unequivocally been asked to do so by the government, in the person of former Minister of Culture and now presidential assistant Vladimir Medinsky.

How the Study Was Conducted

I tried to assess the relative weight of these narratives by comparing the frequency of several terms in the titles, keywords, and abstracts of articles published in Russian-language social science journals:

- pandemic (пандемия)

- special military operation, abbreviated “SVO” in Russian (специальная военная операция, СВО)

- sovereignty (суверенитет)

- gender (гендер)

To do this, I studied Russian-language articles in the ELibrary database that have been published in journals in the three largest social-scientific disciplines: political science, sociology, and economics.

Specific Characteristics of Each Term

Two terms—”pandemic” and “special military operation”—refer to specific phenomena and associated issues.

The other two—”gender” and “sovereignty”—refer to broad research topics.

Of the former two, the term “special military operation” is clearly politically charged. The pandemic should have concerned both liberals and conservatives equally.

Of the latter two, “sovereignty” has in recent years become the main linguistic marker of the official state ideology, a designation of political independence from harmful Western influences and a symbol of an independent political course. “Gender,” by contrast, has been denounced as a symbol of the moral decline of the West. (In this sense, the term “queer” might be a better example, but a search of the RSCI database returns only 108 instances of the term—clearly not enough to analyze its dynamics.)

The situation with “gender” is not as clear-cut as with “sovereignty.” The term may also be used in articles dedicated to exposing “gender ideology.”

However, a brief perusal of the search results in the ELibrary database shows that the number of negative uses of the term is relatively small (at least for now).

“Innovation” versus “Pandemic” and “SVO”

Before 2020, social scientists almost never mentioned pandemics, and until 2022, the same was true of the term “special military operation” (about 10 articles per year).

Then the frequency of use of both terms skyrocketed, almost equaling (in the case of “SVO”) or far exceeding (in the case of “pandemic”) the frequency of the term “innovation”—previously a favorite topic of Russian social scientists.

Dynamics of the Popularity of Terms in Article Metadata (Extrapolation for 2023)

“Pandemic” versus “SVO”

In the first year of each, more than twice as much was written about the pandemic as about the “special military operation.”

- There were 1,950 mentions of “pandemic” in 2020, even though COVID only officially reached Russia in March

- There were 818 mentions of SVO in 2022 (the special operation began in February)

Shifting the political agenda was made easier by the ongoing pandemic.

“Gender” versus “Sovereignty”

Less concrete terms such as “gender” and “sovereignty” have also seen a dramatic shift in usage.

In 2012, the number of mentions for both terms was approximately the same:

- Sovereignty—363

- Gender—350

Then “sovereignty” experienced two visible upswings:

- In 2015, following the “Russian Spring”

- In 2022, after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine

“Gender” rose more slowly, but still noticeably:

- 556 mentions in 2021

But then saw a sharp decline:

- Fewer than 200 instances projected for 2023

Social scientists have clearly sought to avoid uncomfortable topics, or at least uncomfortable terms, opting to replace the word “gender” (гендер) with “sex” (пол), which is considered a more politically correct term in Russian.

Conclusions

Overall, we see that shifts in the political agenda have had a significant impact on the scientific agenda. Russian social sciences have entered a new era, even if practitioners are not particularly enthusiastic about it.

In Lieu of a Postscript: Methodological Shortcomings

It is worth mentioning several limitations of the methodology used.

First, the RSCI search function does not allow you to filter publications by language. Interspersed among the Russian-language results are a number of publications in Belarusian, Kyrgyz, and other languages that use the Cyrillic alphabet. However, these publications generally make up no more than 5% of the total results for a given search.

Moreover, these articles may cause the variation in frequency of a specific term to look less dramatic, but not more so. After all, scientists using these terms outside of Russia are not subject to the same effects of government policy as their Russian colleagues.

Second, the RSCI does allow you to search within individual social and scientific disciplines. Nevertheless, some of the results still come from multidisciplinary publications like university newsletters. Plus, some medical publications market themselves in the same way as economic publications.

Therefore, some of the articles on the pandemic were actually written by biologists or doctors. It should be noted, however, that both groups also write about the “special military operation”—for example, when discussing the best form of psychological rehabilitation for those involved.

I tried to circumvent this by excluding those articles that were also classified as medical or biological when calculating the number of mentions of the pandemic. This produced a conservative estimate of the popularity of the topic, since some of the excluded articles were still on sociology and economics, not medicine.

However, even without these extra measures, the overall picture was quite clear.

Third, 2023 is not yet over and the publication of some articles on ELibrary will be delayed. However, if this delay is approximately the same as in previous years, then at the end of October, when the data were collected, approximately two-thirds of the publications for the current year had been indexed. Taking this into account, I introduced a factor to correct the data and extrapolate the probable value.

Mikhail Sokolov is a sociologist.

0 Comments