Natural sciences vs. humanities: who stands to gain and who will suffer from the conservative swing?

Dmitry Dubrovsky

Photo: The debate over whether an atheist Darwinian can criticize the very existence of God is now protected by academic freedom in the same way that a biology professor’s right to criticize Darwinism is protected by academic freedom. Photo by Fernando Venzano on Unsplash

How similar are understandings of academic freedom across different disciplines—namely social sciences and the humanities, on one side, and natural sciences, on the other?

Differing definitions of academic freedom may impact the effectiveness of coordinated work to defend academic rights and reach academic freedom.

Let us examine the evolution of this concept.

The Evolution of Scientific Freedom

The Middle Ages. During the Middle Ages, the humanities and social sciences developed under the control of the church. A more varied picture emerged in the natural sciences. Key works in some disciplines, such as Euclid’s geometry, written around 300 B.C., were republished without any particular issue. That being said, everyone knows the sad fate that befell Galileo.

The natural sciences became the basis of Science. Humanitarian and social knowledge became the Arts.

19th century. German philosophers Wilhelm Windelband and Heinrich Rickert divided the sciences into nomothetic and idiographic—”sciences concerning nature” and “sciences concerning culture.”

- Nomothetic sciences were based on the establishment of general laws founded on the idea of generalizing the phenomena being studied.

- Idiographic sciences studied key traits in their individual manifestations.

The modern era is marked by the natural sciences’ struggle to gain independence from the influence of the church. The autonomy of European universities, and later universities in the United States, was in large part autonomy from the church as they sought to advance a natural-scientific view of the world, primarily through geography, geology, biology, and chemistry.

This struggle culminated in a settlement agreement: the church lost most of its influence over the universities, becoming limited to dedicated theological departments here and there.

In the United States—a very religious country—the right to freely teach biology has been challenged many times. As a result, the debate over whether an atheist Darwinian can criticize the very existence of God is now protected by academic freedom in the same way that a biology professor’s right to criticize Darwinism is protected by academic freedom.

Interests of the Nation-State

Now free from theology, the humanities and social (or “idiographic”) sciences saw a rise in demand in the emerging nation-state. They became tools for cultivating and maintaining a sense of national unity through education and science.

At the same time, nation-states needed STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) to modernize.

This created a situation that placed sciences, on the whole, in the nation-state’s sphere of interest. But even here, the pressure was uneven.

In disciplines where the state had a direct interest in modernization and the development of a certain technology, it tried to strengthen control over the production of knowledge, but not over the content of this knowledge. In general, the state did not believe in influencing the content of research in physics or chemistry.

In contrast, by the nation-state’s reasoning, history and the social sciences required oversight—and not just over the production of knowledge, but also, to a certain extent, over the content of that knowledge.

This is exactly the same situation that the natural sciences faced in the Middle Ages.

Totalitarian Approach

This oversight is especially apparent in totalitarian states like the USSR.

States like this have established a high degree of autonomy for the natural sciences. Attempts to control the content of the natural sciences—as in the case of Lysenkoism, for example—were an exception to the general rule of the totalitarian USSR. They represented an attempt to control scientists, and not the natural sciences as such.

Meanwhile, many social sciences were completely replaced with ideology.

As a result, by the time the USSR fell, its achievements and global recognition in the natural sciences far exceeded its contributions to humanitarian and social knowledge.

The Different Values of Money

Finally, there was one more circumstance that determined the specific characteristics of perceptions of academic freedom among scientists and teachers in the field of natural sciences: funding.

Research in the STEM field is, on average, several times more expensive than research in the humanities and social sciences. Indeed, the cost of equipment and consumables cannot be compared with the expenses incurred in the humanities and social sciences.

This reality makes STEM scientists and teachers very dependent on funding. In effect, their right to research is dependent on the financial policies of the institution in which they work.

Research shows that in terms of academic freedom, STEM scientists primarily focus on the socio-economic side of the freedom of research, because as a rule, no research is possible without it.

For most humanities scholars and social science practitioners, meanwhile, the main obstacle is financing the work itself, rather than finding funding for equipment or supplies.

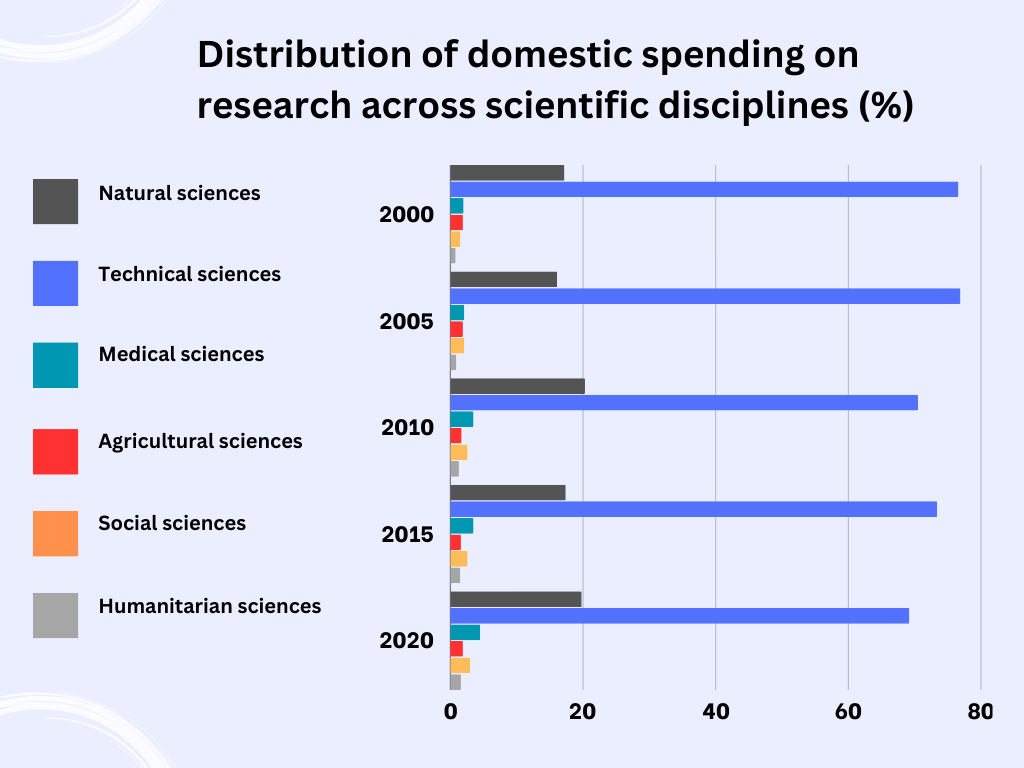

In fact, the distribution of funding across many countries—not just Russia—shows the dramatic disparity between money allocated to the natural and technical sciences, on the one hand, and the social sciences and humanities, on the other hand.

- Humanities and social sciences account for about 5% of total research costs.

- Natural and technical sciences account for around 90%.

Source: ISSEK HSE

Features of Post-Totalitarian Development

This circumstance explains a specific feature of post-totalitarian countries, primarily Russia. This feature is associated with the historical experience of scientists and teachers.

Despite the economic crisis that accompanied the collapse of the USSR, the 1990s became the time of the greatest academic freedom in the humanities and social sciences.

For the natural and technical sciences, it was a different picture. In these sciences, the rights to teach, learn, and especially study were seriously limited in the 1990s by a lack of funding across universities. This had an impact on both teaching and research opportunities in science.

- In those years, the humanities experienced the greatest freedom, since their freedom was “negative”—freedom from

- Meanwhile, the freedom the natural sciences sought was a “positive” freedom—one that required certain guarantees of funding from the state.

Russia in the 21st Century

In the early 2000s, when the government introduced a modernization program for higher education and the sciences, the beneficiaries were primarily STEM teachers and researchers who had suffered during the previous phase.

For humanities scholars, on the other hand, the “return of the state” to the sphere of education and science was more of an unpleasant surprise. Quite soon, the state not only began to interfere in the procedure for producing knowledge, but also set out to control its content.

This only intensified as time went on, particularly after the conservative swing. Thus, the contemporary situation came, to a large extent, to reflect the Soviet experience.

That being said, there are many ways in which this situation differs from Soviet times. In particular, given the ruined autonomy of Russian universities and the undermined autonomy of the Academy of Sciences, the natural sciences now lack the protection that was conferred by the renowned independence from the state that academic institutions enjoyed during the Soviet era.

After February 24

It can be assumed that the outbreak of war only intensified this process.

The humanities and—to an even greater degree—the social sciences are close to a state of asphyxiation.

For their part, the natural sciences, and in particular the technical sciences, are obviously adopting a “wartime stance,” as are Russian universities in general, which have become hubs of war propaganda.

This cannot help but evoke direct associations with the Soviet Union.

On the one hand, the new circumstances guarantee funding for a number of areas of research, especially those related to military equipment and military technology. This may further deepen the differences between different disciplines in terms of their perceptions of academic freedom.

That being said, deglobalization, which has taken over all aspects of Russian science and higher education, will predictably hit those currently involved in the military industry harder.

0 Comments