Why Can Russian Students Not Expect to Have the Same Rights and Freedoms as Teachers?

Dmitry Dubrovsky

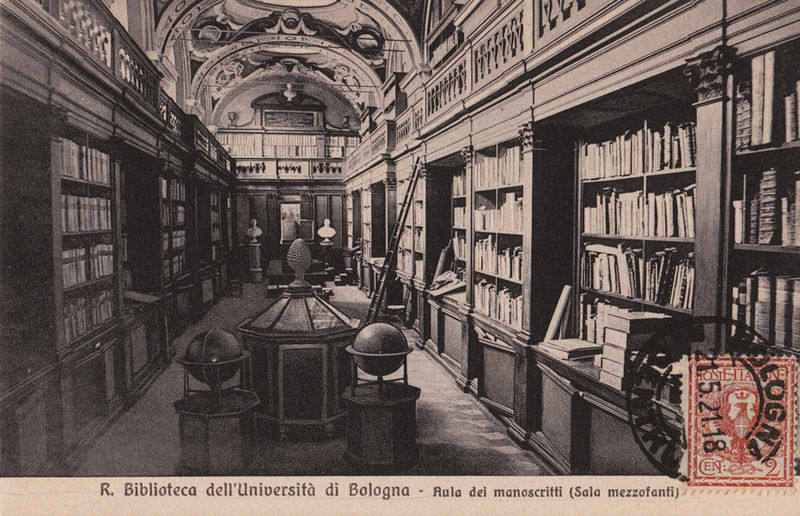

Photos: In the Middle Ages, students hired professors at the University of Bologna. (Unknown author; Wikimedia Commons)

From the outset of university history, there has been no clear answer to the question of who holds the rights of the Universitas community: Is it teachers? Students? Founders?

For example, some of the first universities were originally governed by students. Such was the case, during the Middle Ages, of the University of Bologna, where students were entitled to hire professors.

Fairly quickly, however, power—and rights—passed to founders and teachers.

Who Is a Beneficiary of Academic Freedom?

When academic rights and freedoms were initially formulated, students were not mentioned among those who would enjoy academic freedom. Its main beneficiaries were intended to be university faculty and staff.

For example, in the American Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure (1915), students were referred to only in the statement that teachers had “the right to teach students.” Consequently, for a long time, students were subordinate to teachers.

By the end of the 1970s, there were regulations allowing students to participate in university management. In particular, they could participate in:

- appointing and dismissing teachers; and

- choosing a field for research.

While students’ voice (at least in foreign universities) has become more noticeable since that time, their rights are still not exactly on par with those of teachers when it comes to university life.

“Academic Citizenship”

Students are more than willing to obtain the rights of “academic citizenship.”

Academic citizenship is considered the third component of a professor’s work at university, together with teaching and research activity. This triad was proposed by the American sociologist Edward Shields and developed by the British researcher Bruce Macfarlane.

There is no dispute that teaching is purely the province of professors; students can be involved in it only very narrowly. Academic citizenship is another matter entirely: students, as citizens of the academic republic, may have a right to it.

What Rights Does a Student Have?

The issue is that both globally and in Russia, students are perceived as recipients of knowledge and skills. They gain these from teachers, who have academic rights and freedoms.

In the eyes of Russian legal scholars, students are entitled to:

- transfer from one university to another,

- be readmitted to a university,

- transfer from fee-based education to budget education,

- take a leave of absence,

- study within an individual curriculum, and

- certain others.

These rights are not associated with “academic citizenship.” Rather, they are just guarantees of the “freedom to learn,” which does not carry the power to influence teachers or the content of teaching, including research activities.

What Does the Law Prescribe?

The Russian law “On Higher and Postgraduate Education,” in the section “Academic Autonomy and Academic Freedoms,” says “a student is entitled to gain knowledge per his/her abilities and needs.” The same law confirms the right of students to participate in (1) “management of a university”, (2) “discussions of the most significant issues related to university activities”, and (3) “discussions of the content of education.” In order to follow these prescriptions, every university has formal mechanisms that can be interpreted as “students’ participation in decision-making,” for example:

- students’ participation in Academic Council, and

- the establishment of student councils and trade unions.

What Are Students Allowed to Do?

Unfortunately, many Russian legal scholars, when discussing the inclusion of students in a university’s management system, deny student self-government the status of an independent actor. The following quotation illuminates how they understand the objectives of student government:

“…initiative, creativity, the activity of students shall be directed at solving problems related to education at the university and at developing their professional and cultural competencies, but not at fighting for power, declaring their rights, or protecting interests not related to the university’s goals. In this case, students will definitely find proper support from the administration and teaching staff.”

The goal of such “self-government” is to prevent students from participating in real discussions of issues relevant to them. “Official” student trade unions and other forms of “participation in university management” are becoming a fiction.

What Do Students Need?

Mechanisms to shape an independent student position are discouraged.

Student Trade Unions. Due to the ongoing persecution of independent trade unions in Russia, independent student trade unions face the non-recognition of a “student opinion/position.”

Media. The student newspaper Doxa, which actively discussed the issue of violations of students’ rights, was punished by being stripped of the status of a student journal of the Higher School of Economics.

Scientific Councils. The actual participation of students in Academic Councils is limited. In most Russian universities, there are two or three people who ex officio represent the student body there.

The situation is somewhat different in non-state universities, as well as in the Higher School of Economics, where student activists get into university Academic Councils in noticeably greater numbers. This is reflected in both (1) their activity defending students’ rights, and (2) discussions of various issues relating to student life at a university.

“Pocket” Academic Citizens

In most cases, the student representatives in Academic Councils are so-called “pocket” student trade unions (i.e., those governed and funded by the administration), whose objective is to solve problems relating to education in general rather than to “protect rights.”

Such representatives are an example of student tokenism: they personify “student participation” but do not substantively affect the state of affairs. Moreover, student unions and councils can, if needed, act as bodies through which the administration can organize pro-governmental student initiatives or, conversely, use their representatives to “warn” against participation in “unauthorized rallies.”

When it comes to the expulsion of students from a university on trumped-up grounds, these bodies often take the position of the university administration:

- At Saratov State Technical University, the Student Council did not oppose amendments to the Ethics Code that made participation in protest rallies equal to the violation of academic ethics.

- At St. Petersburg State University, student participation in rallies was likewise considered a violation of the University Ethics Code.

- At the St. Petersburg University of Trade Unions, students’ public criticism of the current situation at the university led to students’ expulsion.

It is indicative that these Ethics Codes are used to limit student criticism not only of universities, but also of the situation in the country as a whole. This is done, for example, on the pretext of “preventing students from using expressions that can fire up conflicts or incite hatred, hostility or resentment in society as a whole and individual groups.”

Docked Grades for Activity

It is more difficult to defend the rights of students persecuted for civic or political activism when the attack is camouflaged by the teacher’s assessment. The simplest approach—and the one most difficult to prove—is to exclude a turbulent student on the pretext of “poor academic performance.” This is particularly true in explicitly political situations.

Thus, LGBT activist Alan Erokh was expelled from Yaroslavl State Pedagogical University for, allegedly, a poor exam result. In a private talk with a student, one teacher admitted that “I am a person who follows orders”—if the administration has decided to expel a student, “a test result is irrelevant.”

Elena Skvortsova, a human rights activist with “Team 29,” was expelled from St. Petersburg State University because she allegedly did not participate in a required practical course. However, the Student Council of the St. Petersburg State University stood up for her, arguing that there was obvious prejudice and noting the “queerness” of the expulsion.

I would not say that a student in Russia cannot defend his/her rights at all. At times—as in the case of the expulsion of three students from the Astrakhan State University for participating in a Navalny rally—courts vindicate rights even in clearly political cases. The expelled students filed a court case: although the local courts upheld their expulsion, the fourth appellate court in Krasnodar overturned the decision and ordered a retrial.

But such a scenario is the exception rather than the rule.

* * *

Students in Russia are at grave risk, especially when it comes to political or civic activism.

In most cases, lacking the opportunity to participate in university management, students cannot rely on institutional protection—even as teachers, who are the formal holders of academic freedom, enjoy it.

At the same time, students are heavily dependent on the speculative or arbitrary application of knowledge assessments and the expulsion mechanism, which can be triggered either by an alleged violation of “academic ethics” or allegedly “poor academic performance.”

0 Comments