The pay gap is most noticeable in research universities.

Darya Gerashchenko and Katerina Guba

Photo: The average teacher receives one-third the salary of their deans and provosts. Photobank Moscow-Live, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

In Russia, there is always a vast gap between administrator salaries and the salaries of those in lower-ranking positions. This is especially apparent in private companies, where income distribution often heavily favors top management.

Universities are fundamentally different from commercial firms. Is there a noticeable gap in salaries between different positions here as well? How has this changed over the past few years?

We found public data about the salaries of rectors, vice-rectors, teachers, and research staff at 200 universities under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education and Science. Using this data, we calculated the salary gap between top managers and ordinary teachers/researchers.

Highest Salaries at Top Universities

Looking at absolute mean salaries, rectors—predictably—earn significantly more than vice-rectors, and far more than teaching staff and researchers.

Rectors’ salaries are highest at research universities. Of the top 20 universities with the highest rector salaries, 12 held the status of a National Research University (NRU) or participated in Project 5-100.

More about Project 5-100 in Victor Pardini’s piece, The “Split University:” Why Do Russian Universities Need Foreign Scholars?

In 2021, the 5 universities with the highest rector salaries were:

- ITMO (formerly the Leningrad Institute of Fine Mechanics and Optics)—1,195,437 rubles/month (US$16,257/month in 2021)

- Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN)—1,035,795 rubles/month (US$14,086/month in 2021)

- Kutafin Moscow State Law University— 1,031,483 rubles/month (US$14,028/month in 2021)

- Russian Technological University (RTU MIREA)—971,615 rubles/month (US$13,213/month in 2021)

- Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University—935,593 rubles/month (US$12,724/month in 2021)

That being said, of course, rectors at many other universities earn much less. In 2021, the lowest salary was 144,798 rubles/month (US$1,969) at the East Siberian State University of Technology and Management. Half of rectors received 341,000 rubles/month (US$4,637) or less.

Vice-rector salaries are usually higher in institutions where rector salaries are higher—the correlation coefficient is 0.87. Similarly, teachers and researchers receive more in universities where administrators have high salaries. The correlation between the average salaries of the teaching staff and the salary of the rector is 0.78, and for scientific employees, 0.56.

In other words, high salaries indicate in absolute terms the overall well-being of a university. There are enough resources to ensure that both teachers and administrators receive high salaries.

The following universities had salaries in the top 20 across all professions:

- Russian Technological University (RTU MIREA)

- Moscow Aviation Institute

- The National University of Science and Technology (MISiS, formerly Moscow State Institute of Steel and Alloys)

- ITMO

- Moscow Power Engineering Institute (MPEI)

- RUDN

Whose Salaries Rose Noticeably

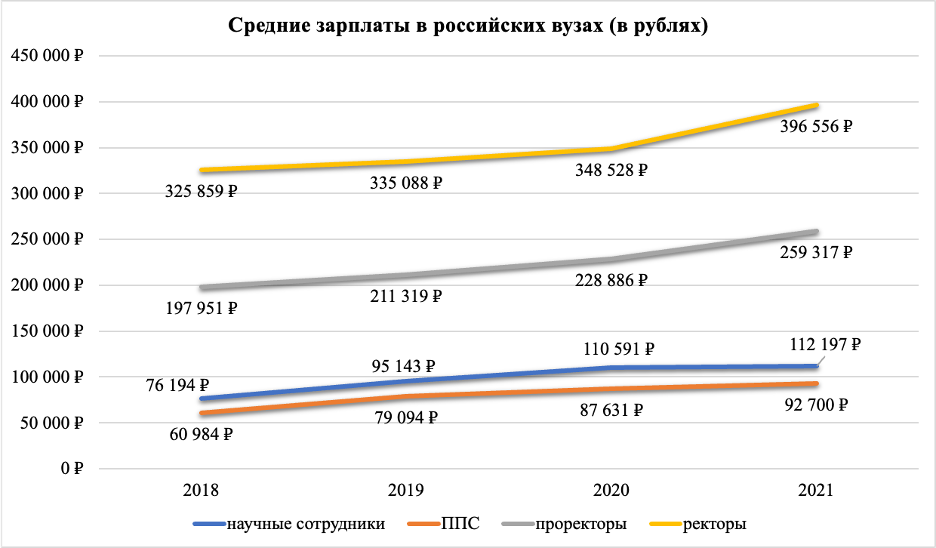

The dynamics over the past four years show salary growth across all employee categories.

If we compare 2018 to 2021, the largest increase is seen in the salaries of teaching staff and researchers.

- Rectors’ salaries increased by 20%

- Vice-rectors’ salaries by 31%

- Research associates’ salaries by 47%

- Teaching staff’s salaries by 51%

This noticeable increase in wages is due in part to presidential decrees on raising the salaries of university employees. In practice, this has often translated to an increase in responsibilities within the same pay bracket, and not to real growth in the incomes of teaching staff. In addition, the mean is heavily influenced by outliers at the top end—even a few professors with very high salaries can greatly inflate the average of the entire group.

While the growth of teacher and researcher salaries has plateaued in recent years, administrative salaries have continued to rise. The salaries of teaching staff increased by 1.8% in 2021, while rectors’ salaries increased by an average of 13%.

Figure 1. Average Salaries at Russian State Universities (in rubles)

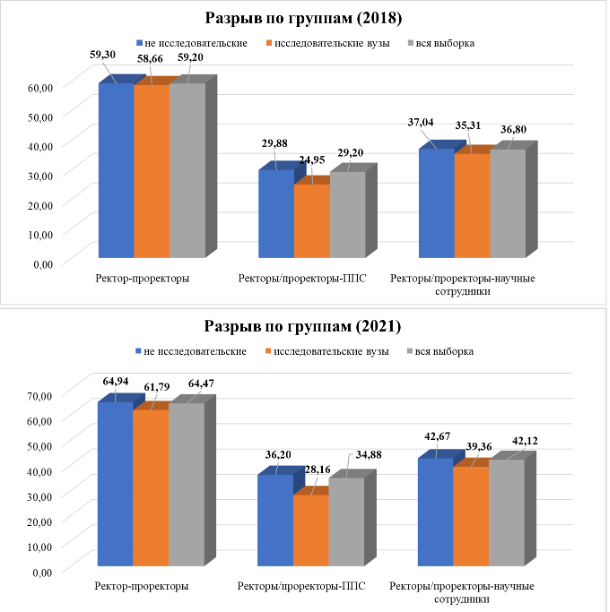

We calculated the percentage gap in average monthly salaries between administrators and teaching staff/researchers for each of the years under study (2018-2021). The data can be interpreted as follows: the average salary of teaching staff or researchers at a given university expressed as a percentage of the average top-level administrator salary (rectors and vice-rectors) at said university.

Figure 2. Salary Gap between Top-Level Administrators and Teaching Staff/Research Associates

Figure 2 shows that in 2018, the salaries of teaching staff were 29.2% of the salaries of rectors and vice-rectors, and the salaries of research staff were 36.8% (mean of entire sample). Until 2020, the trend was toward closing the gap.

In 2021, however, the gap widened. Whereas in 2020 the average salary of teaching staff was 37.2% of the average salary of administrators, by 2021 it had dropped to 34.8%. The average salary of research staff decreased from 47.8% to 42.1%.

Which Universities Have the Smallest Pay Gap?

We expected that the gap would be smaller in universities focused on science (for example, NRUs or former participants of Project 5-100). In these universities, there is a motivation system that allows those employees who produce good results to raise their incomes through publication in prestigious journals. This is how they earn bonuses and allowances.

In reality, the gap is always larger in research-oriented universities, in terms of the salaries of both teaching staff and research staff. Thus, in 2021, the salaries of teaching staff in research universities averaged 28.1% of the average salary of top administrators, while in non-research universities it was 36.2%. This remains true regardless of the university’s specialization or the economic situation of the region.

This result is most likely due to the fact that the ministry allocates more funding to the rectors of research universities, subjectively appreciating the importance of the university and the complexities involved in managing it.

In turn, vice-rectors may also have relatively high salaries, because in accordance with the orders of the ministry, their incomes should only be 10-30% lower than the income of the head of the institution. In other words, if the university rector receives a high salary, the vice-rectors will earn a lot too.

At the same time, the premiums for scientific achievements prevent all teachers and researchers from earning salaries high enough to make the gap less noticeable.

If publications are to reduce the wage gap, then it will be in universities that are less concerned with research projects. When looking at the overall sample, the effect is observed in such variables as the number of articles in journals indexed in Scopus and Web of Science. The more such articles are published in universities, the smaller the gap in salaries. It seems that the value-for-money contract system works—but not at research universities.

The Rector’s Role in Reducing the Wage Gap

Can the ministry take into account the rector’s own wishes when deciding their salary?

It’s entirely likely that it’s harder to attract an outside rector than to elect someone who has worked within the walls of the university for years. Therefore, the salaries of these “outsider” rectors may be higher than those of “internal” rectors. It follows, then, that the pay gap may be more apparent in universities that hire outside rectors.

Similarly, if a rector is elected—and knows that they will be re-elected—and the trust of employees and students is important to them, such a rector will be more inclined to take into account the interests of ordinary university employees, including their salary expectations. By contrast, an outside appointed rector is less dependent on university staff. Therefore, it might be expected that the wage gap would be larger in such universities.

However, the available data do not show this to be true.

* * *

The salaries of rectors at Russian universities vary greatly depending on the university and region.

Over the past four years, the salaries of all categories of employees have increased. The average salaries of teachers have grown most noticeably, but their growth has stagnated over the past year.

In universities, there is a noticeable income gap between top-level university administrators and essential employees. On average, teachers receive one-third the salary of rectors and vice-rectors.

At the same time, the previous trend toward narrowing the gap was no longer evident by 2021. And contrary to all expectations, it is at research universities that the wage gap is most noticeable.

0 Comments