Academic disputes about the guilt and accountability of Russian professors

Dmitry Dubrovsky

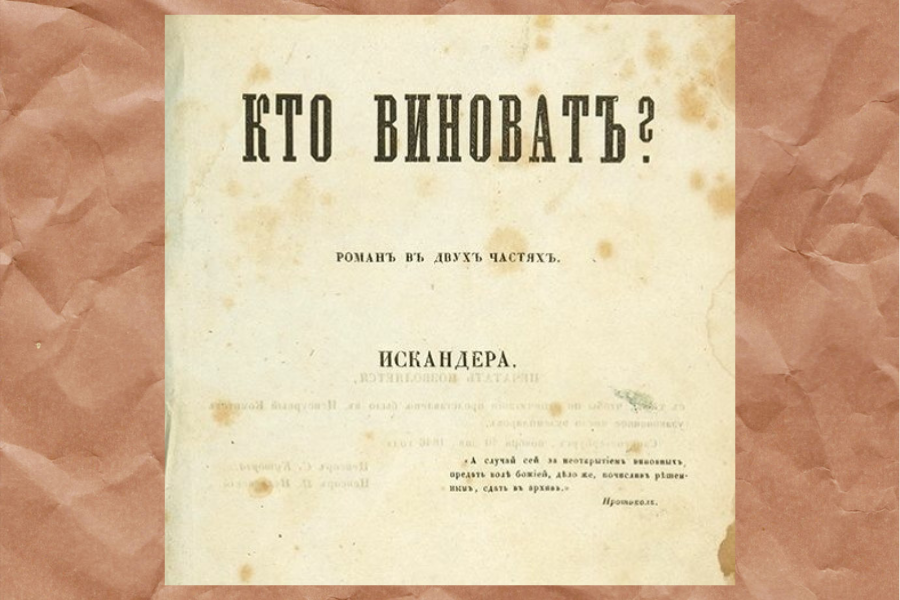

Photo: In elite universities, the high price of freedom was paid for what proved to be a disastrous proximity to power.

Within the academic community, the outbreak of war exacerbated the growing divide regarding the notion of academic freedom and its limits.

Those who—prior to the start of the war, and especially to the “rectors’ statement”—were unwilling to put up with the high degree of servility required of professors resigned and/or left.

For those who remained, the issue of accountability to colleagues, students, institutions or even science as a whole became a priority in choosing a strategy. How were they to respond to the rapidly deteriorating academic climate within universities primarily caused by mobilization in support of the “war party”?

This was particularly relevant in the so-called “elite” universities that had strong ties, in one way or another, to the government—and were therefore subjected to serious tests of loyalty. Among the main guarantors of this special relationship between the universities and the state were Yaroslav Kuzminov, founder and rector of HSE (The Higher School of Economics), and Vladimir Mau, former rector of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA). Both have now ceased to be rectors: Kuzminov in 2021 and Mau in January 2023.

An assessment of their legacies reveals how differently two professors who spent many years working in the institutions these rectors created evaluated the contribution of the system they created to the current crisis of academic freedom.

“Academic Freedom Tester”

In the pages of Novaya Gazeta Europe, former HSE professor Hasan Huseynov opened the conversation about “What a Russian University Should Not Be.” This article made me recall the apt moniker given to Huseynov by another colleague in the philology department: the “academic freedom tester.”

His radical public statements have become part of the history of the Russian struggle for the right to academic speech.

- The incident involving his statement about “cloacal Russian” demonstrated how easily “elite universities” succumb to the powers that be and wield their ethics commissions as blatant tools of censorship.

- Another incident concerning the so-called “justification of terrorism“—also provoked by one of Huseynov’s Facebook comments—showed that professors are quite prepared to participate in the justification and “scientific reinforcement” of their bosses’ censorship, even as it denies the freedom of critical scientific expression.

Complicit Professors

These examples reflect, among other things, university administrations’ complete dependence on the ruling party. The same thing happened in the 2000s, due in particular to the state’s active intervention in science and higher education.

Authoritarian modernization in higher education has created a bizarre juxtaposition between scientific advancement, on the one hand, and a reduction in academic liberties, on the other. By Huseynov’s logic, it wasn’t just the founders of institutions that were actively involved in this process of authoritarian modernization—the professors were also complicit in the creation of systemic inequality.

According to Prof. Huseynov, this system handed out gratuitously high salaries (he refers to them using the criminal slang word gryev, or “warming” in English—a term used to refer to special items and food products given out that would otherwise be considered contraband within the prison walls).

The bitterness of defeat spurred emotional language. According to Prof. Huseynov, “the crystalline dream has been shattered.”

“We Will Still Feel the Institutional Effect”

Evgeny Roshchin, a recent professor at the St. Petersburg branch of RANEPA, has a different view of Vladimir Mau’s legacy.

In his opinion, no matter how one evaluates the rector’s subsequent actions, “…without Mau’s support, the [political science] faculty on the St. Petersburg campus would never have existed.”

Without Rector Mau, it would have been impossible even to conceive of the idea that an international supervisory board would be established on the St. Petersburg campus or that the faculty would have publications in respectable journals—that it would follow what is considered the “normal educational model.”

He does not agree with Prof. Huseynov’s thesis that education in the leading Russian universities was “an illusion and a showcase for the West.” Roshchin sees Mau’s work as significant in the sense that “a small institutional effect from these projects will be felt for some time throughout academia. And serve as a reason to be proud of our graduates.”

Criticisms and Controversy

Sociologist Ilya Matveev immediately responded to Huseynov’s article, reproaching him for “sitting atop his high horse” and ignoring the support campaigns that had once been organized in defense of both Huseynov himself and Rector Zuev of the Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences.

It’s impossible to deny that examples of resistance have multiplied, even in the darkest days of Russian academia—from the students’ defense of the Smolny Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences to the mass support of Rector Sergei Zuev by students and staff.

Former teacher Ilya Kukulin disputes Huseynov’s claims. The gryev about which Huseynov writes, he says, “by no means applied to all HSE teachers.” Therefore, it is misleading to write everyone off as “representatives of a super corrupt corporation.” This greatly simplifies the overall picture and, especially in wartime conditions, supports the popular idea of the collective accountability of Russian scientists.

While agreeing with Prof. Huseynov’s critics, I feel that it is important to mention that they never touched on the main point. This article is a rare example of difficult self-reflection. It is hard for the author to acknowledge that he himself, having worked for many years in Germany in conditions of absolute academic freedom, so readily participated in a system that, in his opinion, not only was a mere simulation (if a successful one) of free academia, but also provided expert assistance to the regime during the peaceful phase of its development.

“Pockets of Effectiveness”

However, the main issue is not so much the accountability of the leadership of elite universities as the accountability of their professors. Many of them easily gave up the freedoms they inherited in the 1990s in exchange for a guaranteed source of income and international connections.

The system that has developed in leading Russian universities was built on cultivated inequality, both financial and administrative. This inequality stemmed from the logic of authoritarian modernization, as beautifully described by Vladimir Gelman.

This inequality was a direct result of a strange mixture of neo-corporatism and meritocracy. Promising projects occasionally popped up in this environment, but they were doomed from the moment they were created.

Starting with the Higher School of Economics, these “pockets of efficiency” began to attract scientists who, for the most part, had no experience of academic shared governance. They usually had only a very general idea of what institutions and academic self-governance practices should be.

Freedom in Exchange for Loyalty

As a rule, the leaders of these projects established structures for interaction with the government that could only be called corrupt.

It is difficult to blame all professors for this. As the Abkhazian writer Fazil Iskander describes it in Rabbits and Boa Constrictors, the inner circle—those sitting “closest to the table”—has always been small. But it was they who decided the fate of the rest.

At the same time, the high degree of freedom guaranteed to employees in these “authoritarian pockets” was effectively converted into loyalty for the authorities. In exchange for their freedom, they had to put up with all sorts of ideological rubbish. Everyone tried to ignore it and considered it the annoying but necessary price to be paid for the ability to do decent work.

The Mobilization of Academia

It is the institutional nature of these universities—where the high price of freedom was paid for what proved to be a disastrous proximity to power—that is, in my view, the main reason for the pogrom we are witnessing.

The previous agreement with the authorities is no longer in force. Real scientific work ceases to play an important role in the union of science and autocracy. Now the autocrats are no longer demanding handouts, but rather complete subordination—the military mobilization of science.

And under these conditions, as the cases of Yaroslav Kuzminov of the Higher School of Economics and Vladimir Mau of the Russian Academy of National Economy and Public Administration show, the “effective managers” of yore are no longer necessary.

Reorganizing the University

Under these circumstances, Russian state universities, especially those that were flagships of higher education, have fallen the hardest. There are some important conclusions to be drawn from this. Indeed, Prof. Huseynov lays them out himself.

The university needs guaranteed autonomy, true independence, and legal protection. It was a mistake to think that an alliance with autocracy would be a route to transforming them. As it turns out, this is the path to the authoritarianization of the university and the collapse of progressive and innovative projects in the field of higher education.

Reorganizing the universities and training staff in the practices of democratic self-government is a task no less important than protecting the cohort of teachers and researchers who will revive free Russian science in the future.

Ilya Kukulin also writes about this: it’s important, he explains, to promote a vision of the professor as a “free thinker who is in dialogue with society.” And the university should think about ways to protect its autonomy from its sponsors’ agendas (which is truly a global challenge to academic freedom).

This will only become possible when a true separation of powers—shared governance—is introduced to the universities. And with this, the desire to replace science with ideology, and professionalism with political loyalty, will naturally vanish.

0 Comments