Instruments of memory politics increasingly resemble instruments of official ideological control over history.

Dmitry Dubrovsky

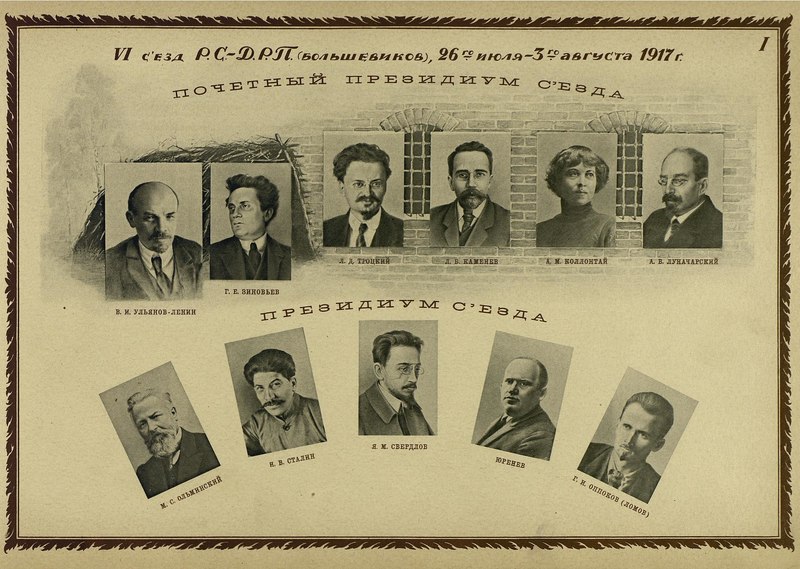

Photo: Album on the history of the All-Union Communist Party (bolsheviks) (1926). Wikimedia Commons

Politics as applied to historical research—“mnemopolitics” or “memory politics”—has claimed an important place in the official rhetoric and practice of the Russian government. President Vladimir Putin’s article on the reasons for and culprits of the outbreak of World War II, the establishment of a special “historical” division in the Investigative Committee, the blatant judicial reprisal of historian Yury Dmitriev—these are just a few examples of the crucial role assigned to history in the ideological construction of the Putin regime.

Memory Laws

The horrors of the 20th century—the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire, the Holocaust, Nazi crimes against humanity—led to what is, from the standpoint of the freedom to conduct historical research, quite a controversial process: Europe adopted special legislation in the area of historical memory.

This legislation falls into two categories.

- First, universal declarations about the importance of preserving the memory of the tragedies caused by Nazism and the equal importance of remembering both victims and perpetrators.

- Second, and more worrisome, memory laws that prescribe sanctions for denying the Holocaust and sometimes even genocidal crimes in general.

The politics of the USSR toward its own population and specific groups therein is not included in the latter category. It is important to note that the USSR was not tried in the Nuremberg process. While there were attempts to discuss the Soviet Union’s crimes (for example, the extermination of Polish prisoners of war in Katyn), the prosecution did not support them (although those charges against the Nazis were also dismissed).

In the aftermath of the collapse of the USSR, it became universally accepted that the crimes of totalitarian regimes should be investigated and punished, regardless of which side the perpetrator was on when they were acting.

For instance, on January 25, 2006, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) adopted Resolution 1418/2006 on the “need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes,” which discussed the responsibility of communist countries, primarily the USSR, for massive human rights violations.

The 2009 Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) resolution “On Divided Europe Reunited” explicitly equates Stalinism to Nazism:

“…in the 20th century, European countries had to contend with two powerful totalitarian regimes, Nazi and Stalinist, which brought about genocide, violations of human rights and liberties, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.”

By the same token, Georgia, Ukraine, Latvia, and Lithuania adopted legislation prescribing sanctions for displaying Soviet and communist symbols that were similar to the sanctions for displaying Nazi ones.

Russia against “Abuses of History”

Russian officials have always reacted to comparisons of the Soviet Union to Nazi Germany with pointed rhetoric. Back in 2009, the head of the Russian delegation to the OSCE labeled the adoption of Resolution 1418/2006 an “abuse of history.”

Today, Russia’s official position can be summarized in the following harsh thesis:

attempts to equate the crimes of Stalinism and Nazism are a way of defaming the USSR and rewriting the results of World War II, as well as undermining the legitimacy of the Nuremberg trials.

It is in order to prevent these “abuses” that the Commission for Countering Attempts at Historical Falsification to the Detriment of Russia’s Interests was created in May 2009.

Historians for the Freedom of Historical Research

The establishment of the Commission sparked considerable opposition from historians and the public alike. St. Petersburg academics, for example, shared plans to create a Freedom of History society that would serve as a counterweight to the Commission. As a result of such opposition, the Commission was never convened and ceased to exist altogether in 2012. The abrupt end to its operations went virtually unnoticed.

That being said, these active protests were not without consequences. For instance, Nikolay Koposov, an involved participant in discussions surrounding the issue and the Founding Dean of Smolny College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at St. Petersburg State University, had to leave his post.

On the whole, however, the Commission’s activity—or, more accurately, lack thereof—hardly affected the freedom of historical research and historians in Russia.

The “Mobilization” of Historians

In 2012, President Putin issued an order to create the Russian Military Historical Society to replace the infamous Commission. One of its primary functions is “facilitating Russian military history research and countering attempts to distort it.” The Society is known for its work maintaining and supporting the official historical narrative.

Slightly more than a year later, in 2014, the “historical” Article 354.1 was added to the Russian Criminal Code. It imposed penalties ranging from substantial fines to prison time for

- “denying facts” established by the Nuremberg process;

- “disseminating false information about the activities of the USSR during World War II;”

- “disseminating information expressing explicit disrespect for the Days of Military Honor and Russia’s memorable dates dedicated to defenders of the Fatherland;” and

- “vandalizing symbols of Russia’s military honor.”

By February 2014, the Free Historical Society had been established, a natural response to the mobilization of “official historians” and the formal discussion of memory laws. Among its goals, the Society listed the following:

- countering “politically motivated attacks” on historical research, especially research on modern history; and

- preserving professional dialogue in this sensitive sphere.

State-Controlled History after Crimea

The conservative turn that Russia took following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 has had a substantial impact on the freedom of historical research and historians.

According to the National Security Strategy published in 2015, “some countries” have manipulated “public consciousness” and falsified history.

At the same time, an offensive against those researching the crimes of Stalinism was launched. The memory of victims was increasingly replaced with the memory of aggressors. This tendency became even more obvious when Perm-36, the only museum in Russia dedicated to the history of political repressions, became state-owned and its staff were replaced.

Another illustrative example is the aforementioned case of Yury Dmitriev, a historian from Petrozavodsk who opened Sandarmokh—where victims of Stalin’s repressions were executed en masse—up to the Russian public. A fabricated allegation recently provided the pretext for increasing his prison sentence to 13 years.

Thus, history is used to strengthen the ideological construction of the authoritarian regime, both outside the country (where the goal is to uphold Russia’s reputation as the victor in the war against Nazism) and within its borders.

The Constitution and the President: About the Right Version of History

The recently adopted constitutional amendments contain a specific reference to defending the right version of history:

“3. The Russian Federation honors the memory of defenders of the Fatherland and protects historical truth. Diminishing the significance of the people’s heroism in defending the Fatherland is not permitted.”

Sociologist Dina Khapaeva notes that “This attempt to write the war myth into the Constitution signifies that the government views regulating memory as a vital objective.”

Finally, the President himself recently authored an article dedicated to the pre-war politics of the USSR and the outbreak of World War II. In it, Putin effectively offered the official version of history—one that is consistent with “historical truth.”

The Beginning of Realization

A practical realization of these ideas is quite clearly outlined in ex-Minister of Education Olga Vasilyeva’s address to the recent “History for the Future” forum. She laid out the two most important victories in the battle for Russian history:

- The victory over the Pokrovsky school. This was “won personally by Joseph Stalin.”

- The victory over Soros. The second battle began in the 1990s, when “…Soros was teaching our children with Kreder’s textbook,” “…freedom and pluralism were written into the law on education as core values,” and “…legislative bodies did not have the right to defend any textbooks.”

This is the legacy Russia is explicitly rejecting in this new stage of modern memory politics, much to the joy of the former Minister of Education.

Sergey Glazyev, advisor to the President, expresses similar views. In his recent article in VPK, he insists that “Fomenko’s new chronology [a repeatedly debunked “alternative timeline of world history” – Ed.] provides an excellent logical foundation for restoring the historical memory of the Russian world… It fits completely into the scientific method of formulating a consolidated ideology, as well as into the construction of a new image of Russia’s future.”

Within such a paradigm, historical research becomes decidedly irrelevant: Orthodoxy replaces criticism; criminal code articles are levied against the opponent instead of engaging in educated debate.

Glazyev further contends that “Normative principles and values expressed through legal norms will organize society not only thanks to the power of tradition but also thanks to the oversight of the law enforcement authorities.”

In accordance with this idea, the Investigative Committee recently announced the creation of a special division for investigating crimes related to the falsification of history.

Read more in Ivan Kurilla’s “What kind of history will investigators write?”

* * *

In response to Glazyev’s article, renowned Russian historians, including two academics and three heads of universities, declared that “such an approach will destroy the system of humanities and social science knowledge in Russia. This might prompt all true researchers of the past to leave their profession…”

“…Research and scientific institutes for acquiring, accumulating, and utilizing objective knowledge about the past are an essential precondition for healthy political governance and the collective wellbeing of any society.”

Instruments of memory politics (“mnemopolitics”) increasingly resemble the instruments of official ideological control—including, now, over history. This directly threatens academic freedom. Mnemopolitics is incompatible with free historical research.

0 Comments